Why the lack of urgency and tepid policy support to date, especially in such a sensitive political year ahead of the 20th Party Congress? We can think of several factors, all inter-related and essentially stemming from China’s policy regime shift that strives for higher quality and more sustainable growth. In this analysis, we will look at:

- Beijing’s new policy regime, how changing demographics underpin it, and why large-scale infrastructure stimulus no longer has a seat at the table

- How crosscurrents emanating from “fragmented authoritarianism” and “Top Level Design” continue to permeate policymaking

- How these crosscurrents, overlayed with multiple (and often conflicting) policy objectives, are likely creating bureaucratic inertia and delayed policy implementation

- Why Beijing will need to finetune its policy apparatus to better respond to economic risks, with some potential clarity arising out of the 20th Party Congress.

The CCP’s policy regime shift reflects its quest for higher quality growth. The 2017 Party Congress represented the start of a policy regime shift from “growth first” to “balancing growth and sustainability”. The 14th Five-Year Plan in 2020 reinforced this shift, emphasizing the need to de-risk and deleverage China’s financial system and broader economy. Last year, another layer of economic and social goals emerged from Xi Jinping’s Common Prosperity program, which aims for less income inequality and improved livelihoods for households. Regulators have also targeted property developers with the so-called “Three Red Lines”, aimed at capping leverage as measured by three balance sheet metrics. As elevated home prices have been a major source of economic inequality, the crackdown on developer and household leverage is consistent with Beijing’s broader de-risking campaign and Common Prosperity program, which ultimately seek to improve housing affordability. All these efforts suggest a higher tolerance for lower growth going forward as Beijing attempts to rebalance China’s growth model away from credit-driven investment and the property sector to new engines of growth including consumption and services, “greener” and “new economy” industries emphasizing innovation and new technologies. Under the new policy paradigm, structural reforms that enhance productivity and competitiveness over the longer term are a key, strategic priority given China’s looming middle-income trap and more adversarial global backdrop, particularly with the U.S.

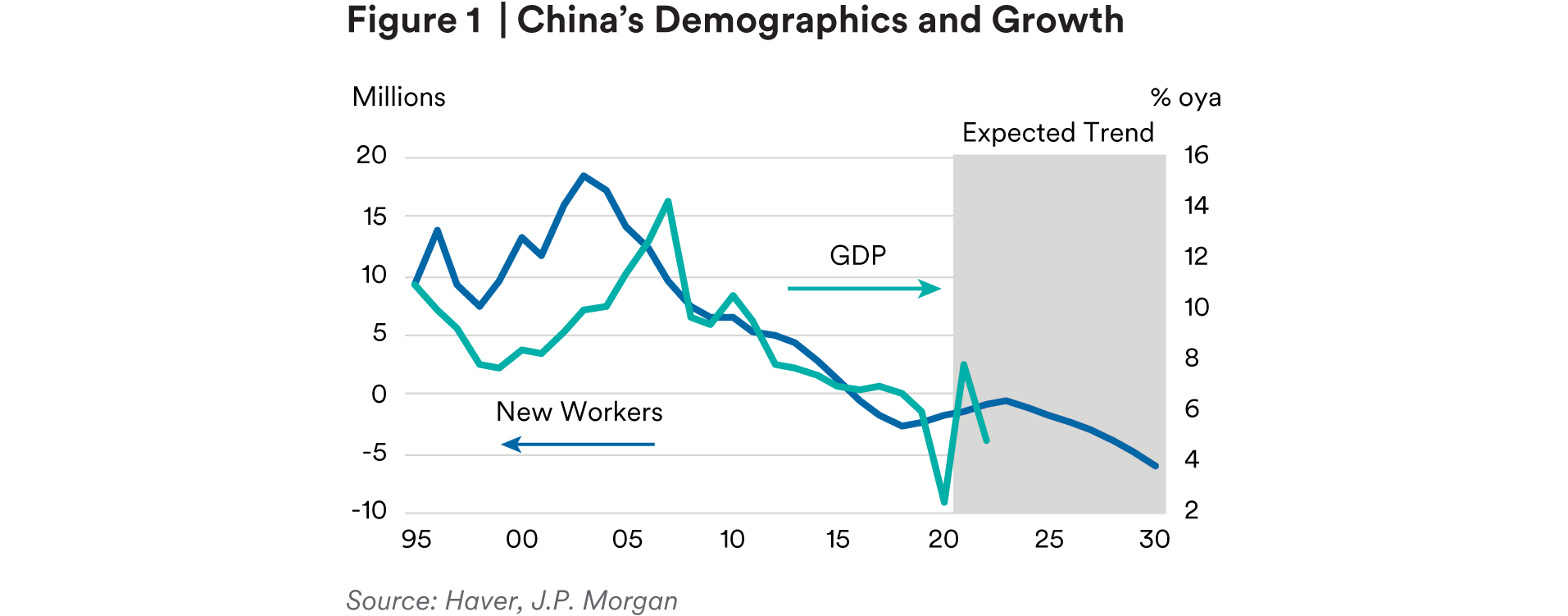

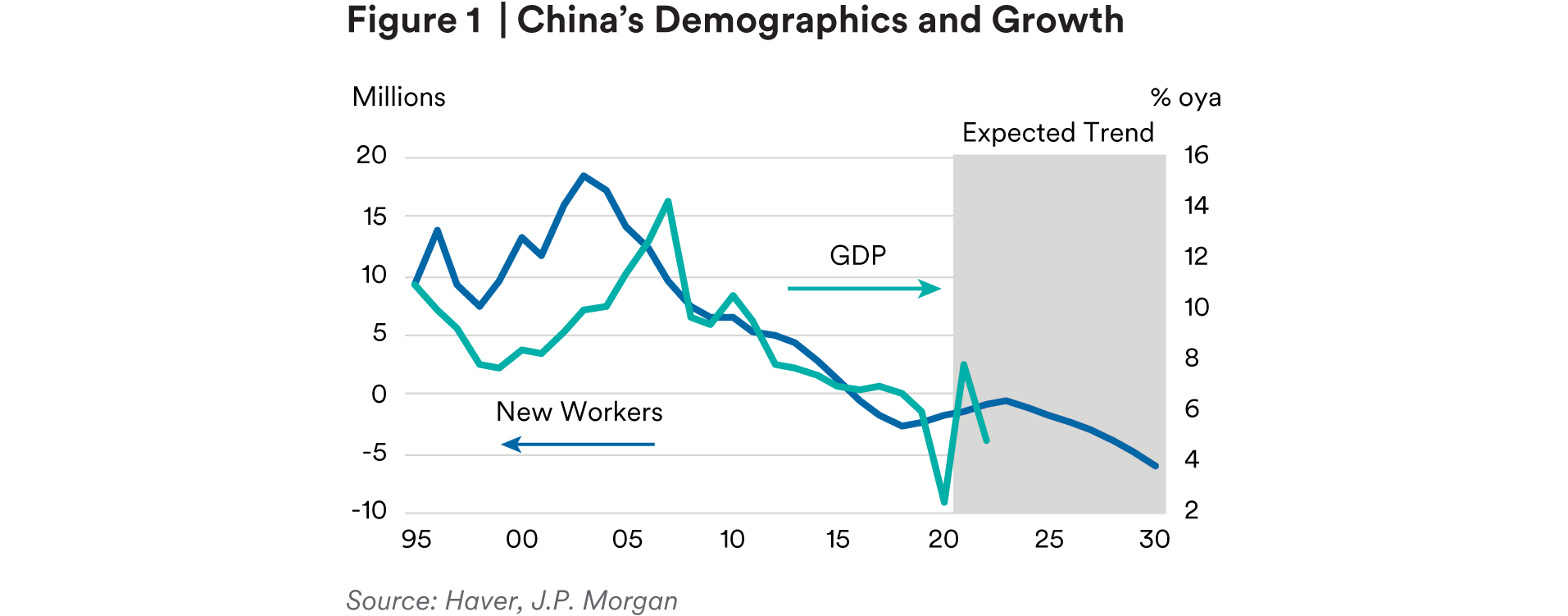

Changing demographics complement the new policy regime. Policy is primarily driven by conditions in the labor market. Whereas in the past, the CCP’s top policy goal was to sustain strong growth to absorb labor supply and maintain social stability, these pressures have eased as the economy has matured and the working-age population has shrunk. In the early 2000s, an average 15 million new workers were added to the labor force every year whereas today China is losing about 1-2 million workers annually (Figure 1)1. Although labor supply has shrunk, new workers today are more skilled and thus new jobs in higher-value-added industries and services are needed. To maintain social stability, the CCP’s key priority has thus shifted from producing lots of jobs to creating higher-wage jobs in key “new economy” sectors.

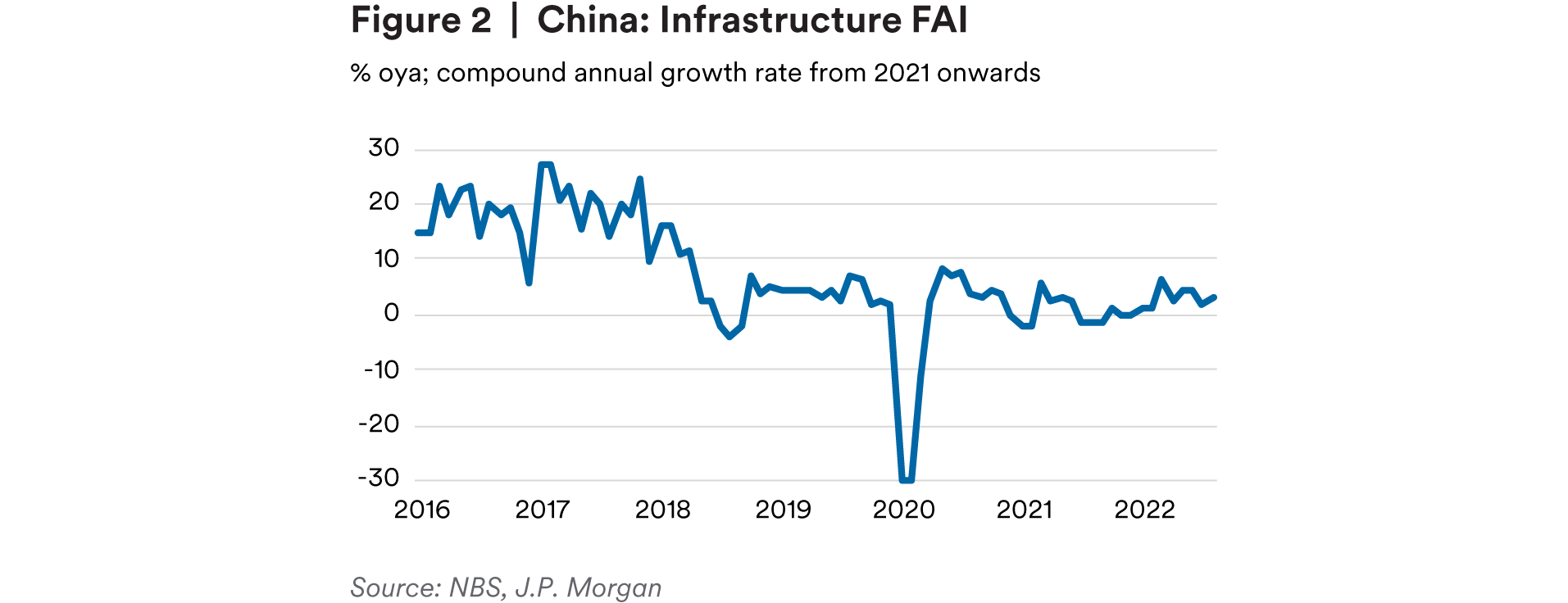

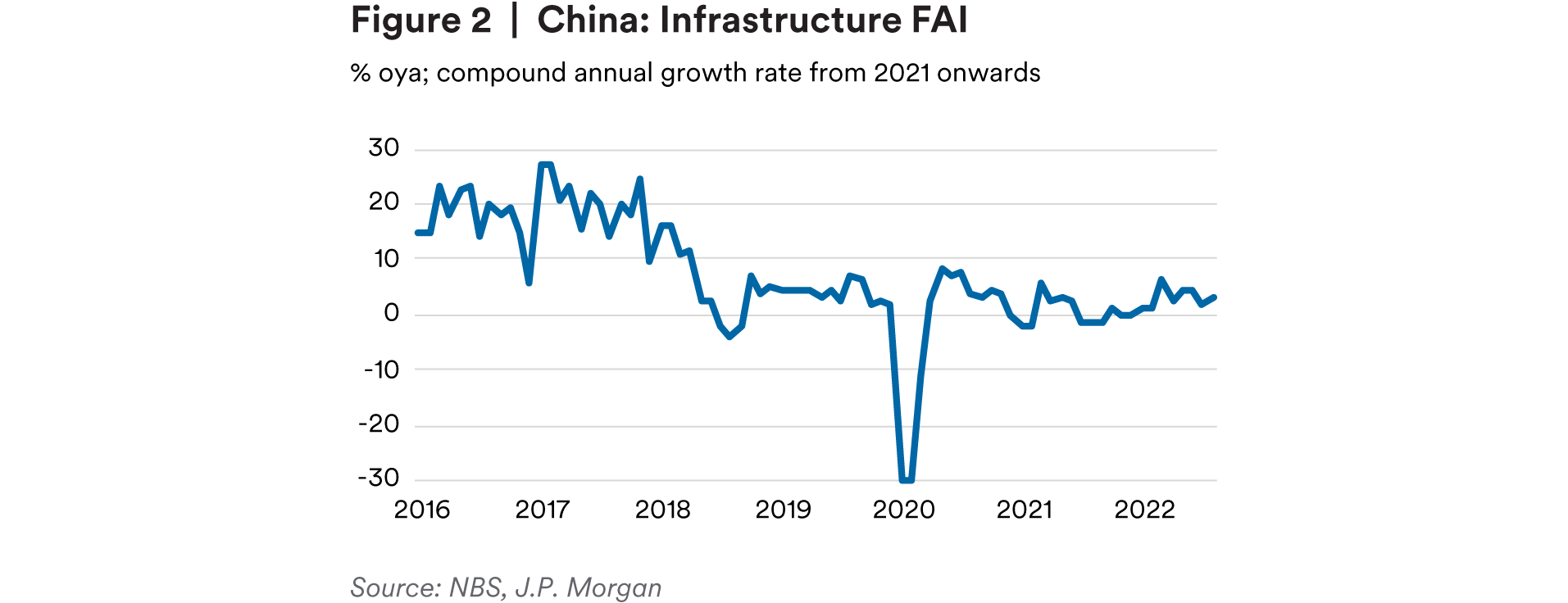

The days of large-scale infrastructure stimulus are over. Credit-driven infrastructure spending was politically discredited following Beijing’s bazooka stimulus post-Global Financial Crisis, which led to wasteful investment, overcapacity, accumulation of local government hidden debt and rising banking sector non-performing loans. This was a key trigger for Beijing’s lurch toward a new de-risking regime and heightened regulatory scrutiny, particularly around infrastructure spending. Beijing aggressively clamped down on the use of Local Government (“LG”) Investment Vehicles, introduced a more regulated municipal bond market and narrowed the pool of qualified projects that met minimal return hurdles. Within the political hierarchy, the introduction of a lifetime personal accountability system meant that local government officials associated with wasteful infrastructure projects would be blacklisted and potentially relieved from duty. Policy support via infrastructure spending has thus fallen out of favor. This was all too evident last year, when, despite an increased LG bond quota, infrastructure investment barely budged. This year’s stepped-up infrastructure spending to buffer the weak property sector will also be modest by historical standards.

Beijing’s policymaking apparatus faces underlying crosscurrents. In our view, another reason for piecemeal policy roll-out over the last couple of years has been Beijing’s transitioning policymaking apparatus. On the one hand, Beijing’s fragmented authoritarianism (“FA”) model encourages a consensus-driven, decentralized approach to policymaking and execution. On the other, Xi Jinping’s “Top Level Design” has led to more centralized control and oversight, creating fundamental crosscurrents in the policymaking process. The latter has been further complicated by Beijing’s policy regime shift, from a single to multiple (and often conflicting) policy objectives at present. Given these overlapping and seemingly contradictory policy impulses, it is likely that speedy and effective policy implementation has been compromised at times.

The FA model is a decentralized and consensus-driven policy structure. The common perception is that policy implementation in China is centralized and “monolithic”; in reality, it is decentralized with overlapping inter-agency involvement and competing objectives. For investors this can be confusing especially under the assumption that Xi Jinping has progressively centralized power under his tenure. This can largely be explained by Beijing’s FA model where policymaking occurs within the authoritarian framework of China’s one-party system but is a fragmented process of bureaucratic bargaining between the CCP, government and military (Figure 2).2 As there are no independent courts to enforce jurisdiction or interpret central government directives, various arms of the state in local jurisdictions resolve disagreements through negotiation and bargaining.3 If the latter prove intractable, they are escalated to higher levels of government or the CCP until a resolution or compromise is reached. Hence, the conventional view of a centralized, efficient policy process under the guidance of the CCP “is no more than an illusion”. 4

“Top-level design” has likely created some policy hesitancy. It is impossible for the CCP to be immersed on every policy issue at every level of government across China. Indeed, consistent with the FA model, there is tolerance for flexibility and experimentation in the “tactics” adopted locally to advance CCP goals and strategies.5 That said, there is also a tendency for local officials to try and shape their own interpretation and implementation of CCP central directives. It has thus become Xi Jinping’s mission to improve Beijing’s ability to monitor and control the actions of local officials to improve compliance and reduce deviation from CCP policy objectives or in some cases face disciplinary action. “Top-level design” has enabled greater centralization of decision-making processes via new and existing central leading groups chaired by Xi Jinping, centralizing power in the top leadership perhaps more than ever before.6 This more disciplined political atmosphere has likely led to policy hesitancy and inaction, compromising local officials’ ability to enact policy quickly and efficiently for fear of overstep and possible impingement in some cases. While “top-level design” can be credited for pushing through difficult economic reforms and overcoming entrenched vested interests, it has arguably created a new set of policy challenges, especially in cases requiring speedy and effective response, for example in the early days of China’s COVID outbreak in Wuhan.

Multiple (and often) conflicting policy objectives may also delay implementation. Whereas policymaking was more straightforward in the past as Beijing sought growth maximization to absorb a growing workforce, the new framework of multiple policy objectives requires an increasingly delicate balancing act that aims to deliver on more fronts. Officials are now given multiple, mutually exclusive objectives, although myriad goals can at times conflict with one another. For example, property- and de-carbonization policies involve no less than eight and nine separate government entities while vertical reporting lines and accountability mean that each have their own priority goal, all of which must be streamlined until compromise is reached. Earlier this year, local officials faced contradicting mandates to spur growth while also containing the pandemic through strict ZCP. Dozens of local officials were sacked for failing to contain outbreaks, while at the same time overzealous officials also met disciplinary action for disrupting local supply chains and bringing economic activity to a standstill. Another related example is the tech sector, where policy shifted suddenly from too little to too much regulatory scrutiny within a short amount of time, resulting in a sharp slowdown in the sector that ultimately forced authorities to backtrack.

The policymaking apparatus likely requires more seasoning and fine-tuning. In our view, Beijing’s shift to a new policy framework of multiple objectives amid underlying crosscurrents from the FA model and “top-level design” has created a more complex environment for policymaking. Going forward, the policy apparatus will likely adjust to the new policy regime through more inter-agency coordination and enhanced governance, although this will likely take time via more trial and error. A good example of fine-tuning was the establishment of the Financial Stability Committee to improve coordination amongst financial regulators. New regulation of internet platforms is mostly on hold. More recently as the Omicron virus started spreading in March, there were many reported instances of poor coordination and planning. The ZCP apparatus has in recent months become more flexible and refined, helping to minimize economic disruption. More examples of inter-agency coordination have also emerged, for example, recent inter-ministerial conferences on the development of the digital economy and on family planning policies. Beijing has also warned against “one-size-fits-all” approaches, allowing LGs more flexibility in tailoring implementation of climate goals.

Conclusion

The FA model, coupled with more centralized CCP oversight, co-exist with an increasingly complex policy regime that seeks to balance Beijing’s economic, political, and social goals. In our view, the policymaking apparatus is experiencing growing pains, at times impeding quicker and more effective policy implementation, likely contributing to China’s patchy growth recovery this year. Meanwhile, Beijing’s more pragmatic turn to head off growth challenges in recent months has led to expectations of more policy reversals to support the property sector and the economy more generally. While we think this more accommodative stance will persist into next year, it is unlikely to mark a departure from Beijing’s longer-term de-risking priorities and Common Prosperity goals. Next month’s 20th Party Congress will likely confirm this view, as well as provide some clues on how Beijing will finetune the policy framework to better respond to China’s economic cycles in coming years. Regardless of the more pragmatic turn in support measures in recent months, we believe this year’s measured and piecemeal policy response is a harbinger for things to come, reflective of China’s maturing economy and changing policy priorities.

Endnotes

1 China’s Regime Change, Haibin Zhu, JP Morgan Securities LLC, October 8, 2021

2 “Bureaucracy, Politics and Decision-Making in Post-Mao China”, Kenneth Lieberthal, David Lampton, University of California Press, 1992

3 Christopher Beddor, Gavekal Dragonomics, August 2022

4 “The End of Fragmented Authoritarianism? Evidence from Military-Civil Fusion Policy under Xi Jinping”, LIM Jaehwan, Professor, School of International Politics, Economics and Communication, Aoyama Gakuin University, January 23, 2021

5 Thomas Neil, EurasiaGroup, August 2022

6 Christopher Beddor, Gavekal Dragonomics, August 2022

Disclosure

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors.

This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as of the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

All investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results.

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address 1 Angel Lane, 8th Floor, London, EC4R 3AB, United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

MIMEL: For investors in the EEA, this document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited (“MIMEL”), authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland (registered number: C451684), registered address 20 on Hatch, Lower Hatch Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. This document is approved by MIMEL as marketing communications for the purposes of the EU Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments (“MiFID II”). Where MIMEL does not have an applicable cross-border license, this document is only intended for, and may only be distributed on request to, investors in the EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under MiFID II, as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 102-0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) under the registration entry Director General of the Kanto Local Finance Bureau (FIBO) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong S.A.R.: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”). MIAL is licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission for Type 1 (dealing in securities), Type 4 (advising on securities) and Type 9 (asset management) regulated activities.

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

1 MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”) is MetLife, Inc.’s institutional management business and the marketing name for subsidiaries of MetLife that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/or unaffiliated/third party investors, including: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), and MIM I LLC and MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited