This paper covers several risks to our baseline view, with political risks being a recurring theme and our key ascendant concern. As countries challenge the U.S.-dominated economic world order, geopolitical tensions and election risks—and whether they resolve or deteriorate—are likely to play an outsized role in the global economy in 2024.

Risk 1: U.S. Debt Troubles

Fiscal risks have risen to the fore in the U.S. In August 2023, Fitch downgraded the U.S. debt to AA from AAA, leaving Moody’s as the last of the three rating agencies still rating U.S. credit as AAA, although it did recently revise down its outlook to negative. As we discuss in our piece on U.S. debt, ratings pressure likely remains to the downside. Compared to its Fitch AA peers, the U.S. has a much higher debt-to-GDP ratio.1 Furthermore, ratings agencies have recently given increasing weight to fiscal processes in looking at the U.S. debt, and the debt ceiling debate at the end of 2024 has the potential to be more disruptive and economically problematic than recent threats of government shutdowns. A downgrade by Moody’s may push a more material repricing of U.S. credit and a diversification away from Treasuries.

Increased geopolitical risks have the potential to exacerbate the debt situation. In 2022, CBO data show that the government spent 3% of nominal GDP on defense, but ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East and increased tensions with China have the potential to push up spending. Although the spending increase may be small, the country already has levels of debt that, as a share of GDP, surpass previous peaks seen in 1943 and 1944 during World War II.2 More direct engagement in conflicts has the potential to worsen the fiscal situation along with the typical economic shocks brought on by conflict.

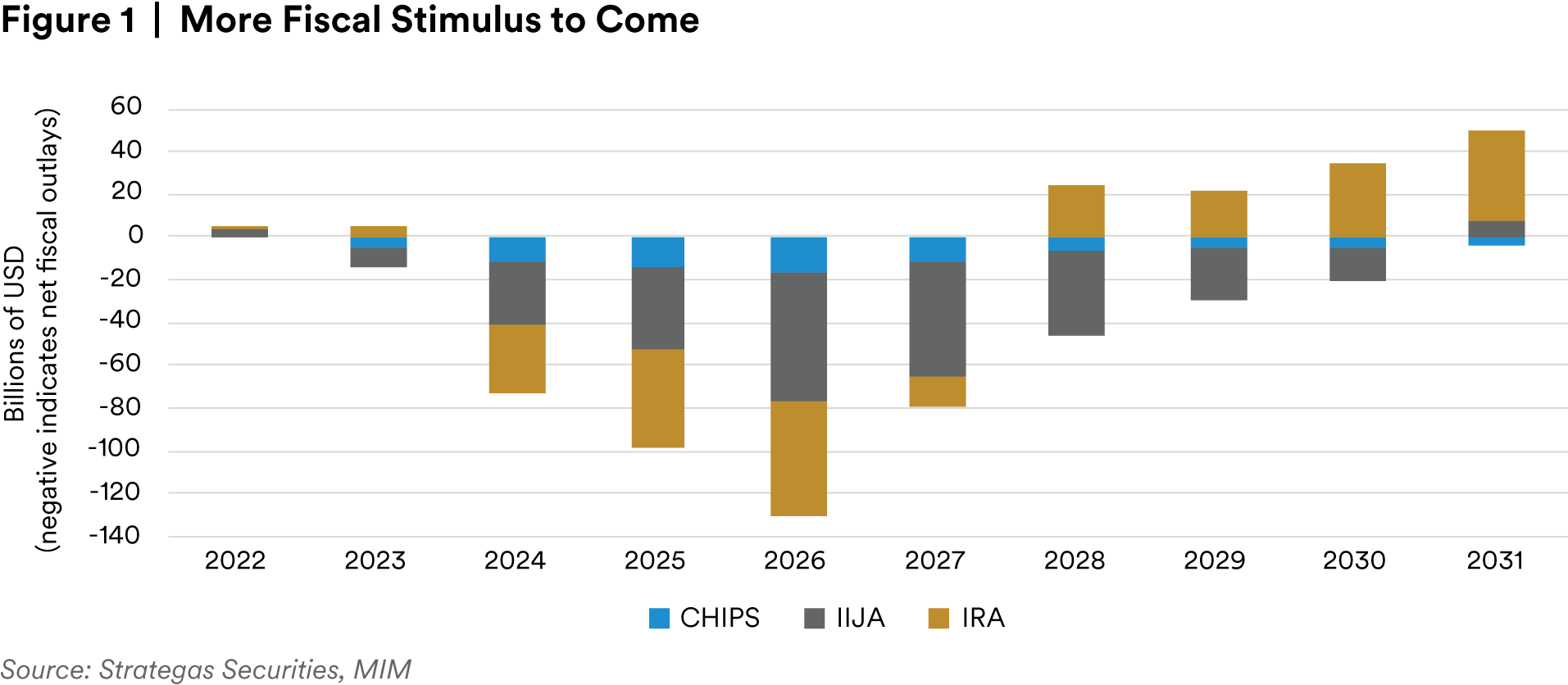

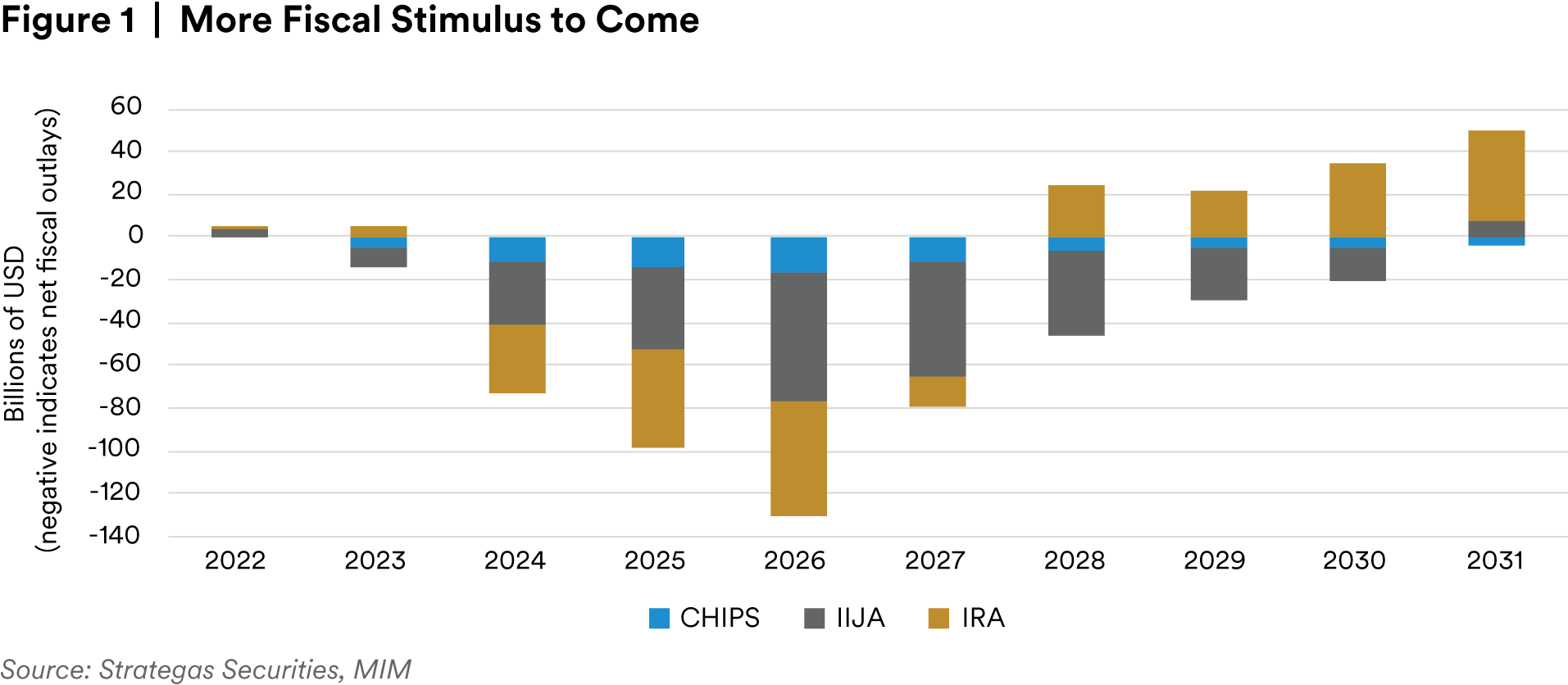

Another concern is that industrial policy actions have been gaining momentum globally, and the growth of protectionist policies could—and to some extent already has—become a competitive cycle that pushes up U.S. spending. In 2023, GDP saw a boost from fiscal spending due to the U.S.’ three recent industrial policy acts, but the spending from the bills is expected to ramp up further until it peaks in 2026, meaning further stimulus effects may be coming. While the trend of increased spending may be a bane for the growing debt in the longer run, it could support a softlanding in the shorter run.

Risk 2: Manufacturing Recovery Creates a Soft Landing

The ISM manufacturing index has shown improvement in the second half of 2023 after spending the first half of the year in contraction territory.

It may be possible for manufacturing to save the economy from a recession by improving even as services weaken.

In an ordinary business cycle, the services sector would have seen negative growth by now, given the deep and persistent decline in the manufacturing sector. But this time really has been different from the consumer’s perspective. The current manufacturing decline has not been driven by general consumer weakness—as it usually is—but by a shift by consumers from goods (during the pandemic) to services (after the pandemic). Manufacturing weakness this time has also been driven by supply chain tightness and the inability of manufacturing companies to fulfill orders and take full advantage of consumer appetite.3

Because of the unique effects of the pandemic, we shouldn’t expect the patterns this time to necessarily fit the patterns of prior cycles. In fact, it may make it more likely that we avoid a recession. If services were to begin contracting now, it would be against the backdrop of an improving, less contractionary manufacturing sector. The asynchrony between goods and services consumption patterns might diversify the economy. If goods and services take “turns” in going into demand-driven recession, then the overall economy as a whole may escape a true recession.

Such asynchronous behavior means that the effects of each sector’s weakness would be diffused. This happened most recently in 2015, when the manufacturing sector experienced a downturn while services continued to expand.

Separately, increased government spending and incentives toward the manufacturing sector could help avoid an economic downturn. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) bolstered 2023 GDP via fiscal stimulus and increased investment, but the full stimulus of these acts is yet to be realized. The IRA was mildly contractionary in fiscal year 2023 due to a new minimum tax, and the total estimated fiscal year 2023 outlays for all three Acts are just $9 billion. For comparison, the estimated deficit impact for fiscal year 2024 ramps up to $73 billion, with a potentially larger impact on GDP.4

If investment remains supported into next year, the case for a soft landing becomes more plausible, especially if inflation continues to moderate.

Risk 3: Resurgence of U.S. Inflation

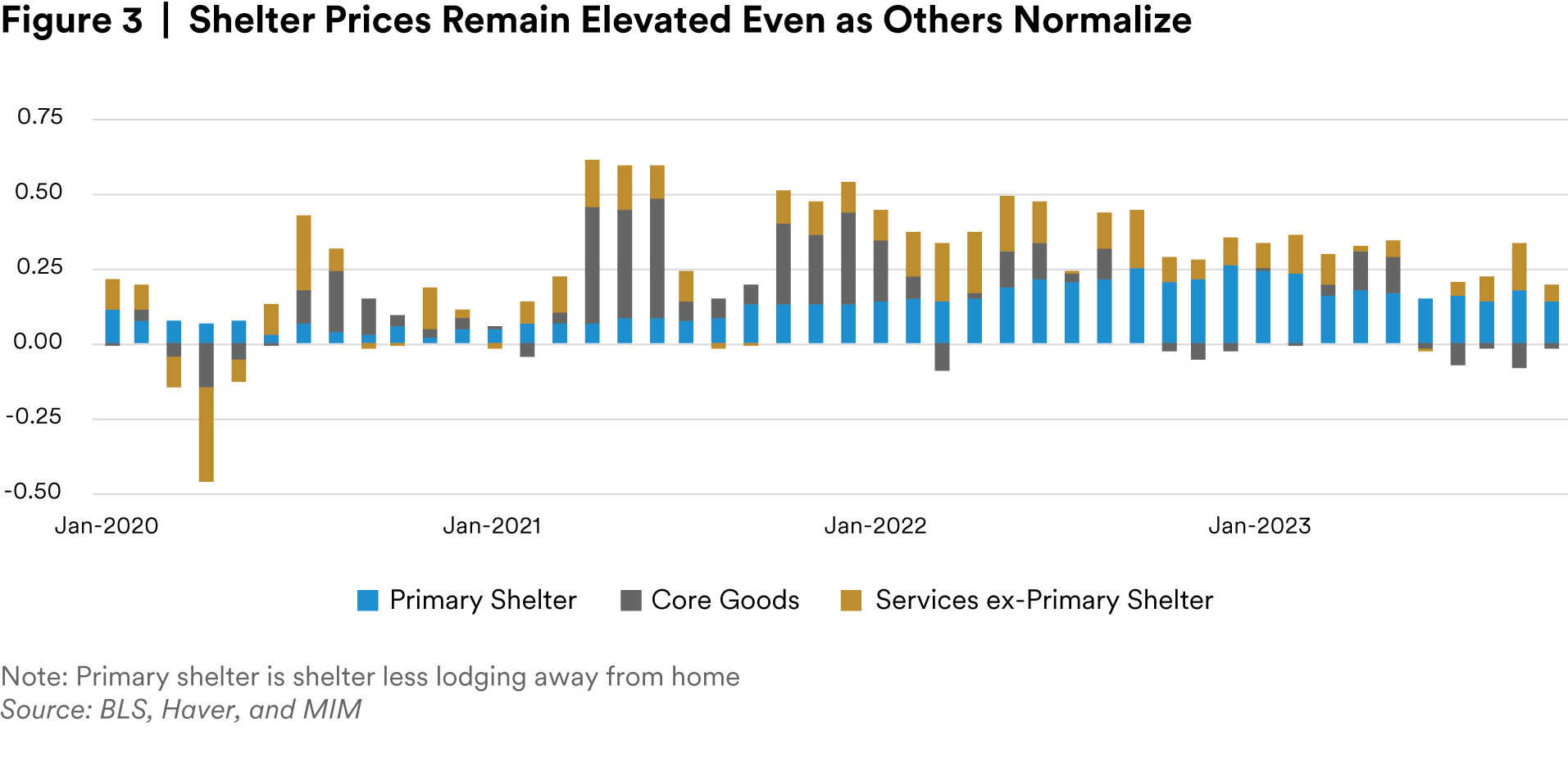

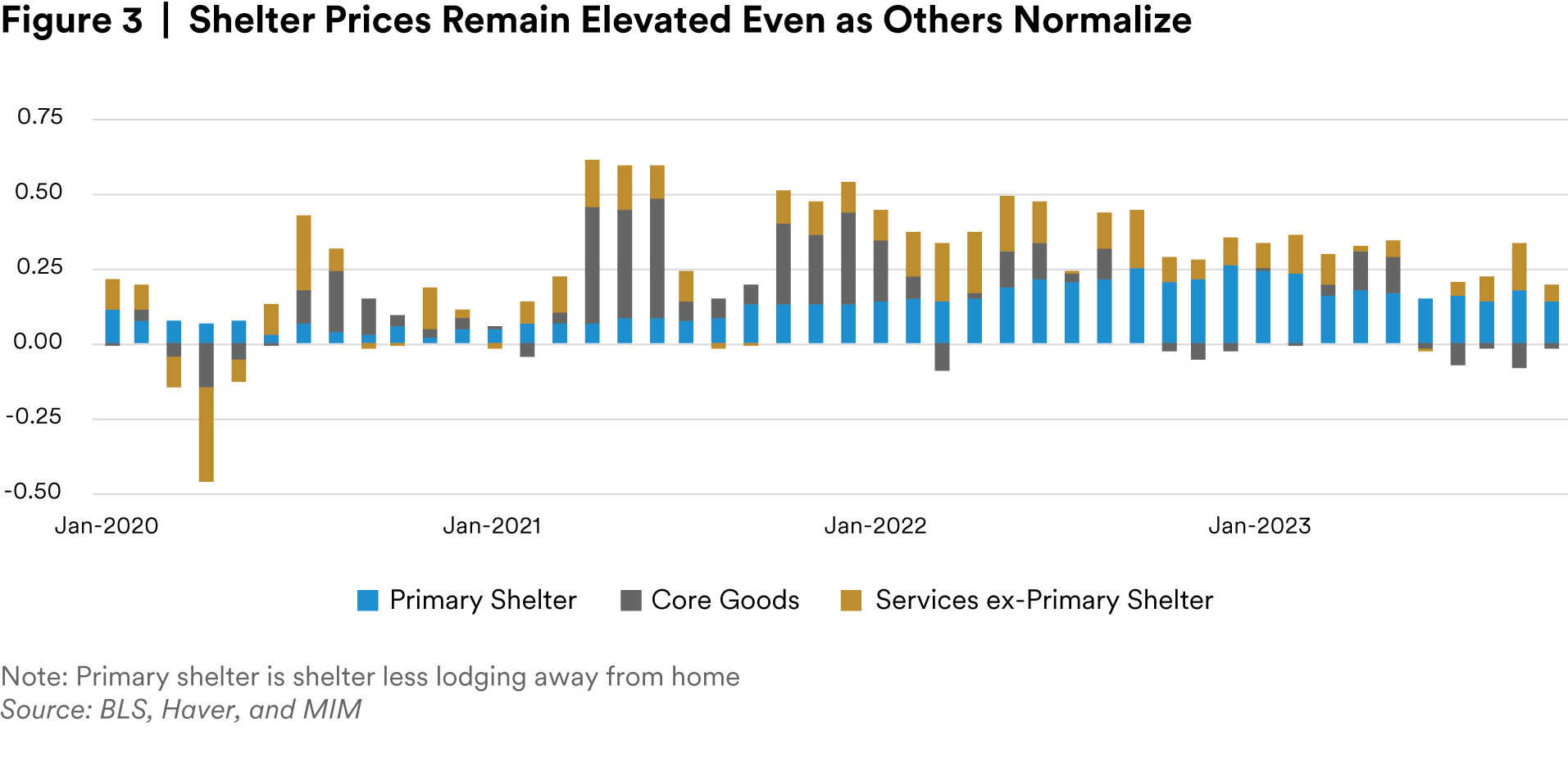

Core inflation has, in recent months, exhibited a promising trend toward 2%. Macroeconomic conditions and Fed policy indicate that this trend is likely to continue. However, we remain on guard against the risk of a higher impulse in inflation.

There are at least four specific channels through which price increases could start to accelerate, and two broader trends that could cause generalized price increases.

First, shelter inflation may continue to be abnormally high. With low inventory and sluggish construction, home prices have remained stubbornly high. This could prompt continued high shelter inflation for at least some part of 2024.

Goods price deflation may be coming to an end. Used car prices have declined 14% since their January 2022 peak. Although used car prices are still above long-run trends, their negative contribution to CPI has been tapering off. If these negative contributions become zero or positive sooner than we expect, then this will no longer act as a counterweight to other line items.

Oil prices remain a point of serious vulnerability, even though the markets have largely adjusted to the current state of geopolitical events. Geopolitical tensions remain particularly concerning (see Risk 4 below). Further, the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is only half filled,5 meaning the U.S. is more vulnerable to external fluctuations than usual. Although central banks tend to look through headline inflation in favor of core inflation, oil prices do tend to spread to core inflation items—transportation in particular.

Finally, property and casualty insurance increases are still working their way through the economy. Insurance prices are rising. As drivers and homeowners renew their insurance policies, new contracts are reflecting higher repair and replacement costs. Higher homeowners’ insurance costs are also increasingly reflecting greater risks due to climate change. With insurers pulling out of many markets, as well as tightening their standards, prices have been rising and may continue to rise.

In addition, at least two broader trends threaten the possibility of moderating inflation. One, already alluded to in the property and casualty insurance prices discussion above, is climate change. Aside from these considerations, the energy transition requires the rebuilding of certain, quasi-redundant, infrastructure. One example is charging stations— the energy transition effectively requires a massive investment in overlaying a nationwide network of charging stations over the existing network of gas stations. The duplicative nature of this process means that the productivity benefits are likely to be lower than the equivalent investment in an altogether new area.

As we argue in Disengagement, Division, or Diversification, a disengagement scenario—with an inward, industrial policy focus—may be taking hold. Firms and government actors have already begun allocating money toward infrastructure and construction of domestic semiconductor capabilities as a result of industrial policy. If the tight labor market were to persist, these expected outlays could become inflationary, particularly in certain sectors of the economy.

Risk 4: Geopolitical Tensions Boil Over

Current conflicts between Ukraine and Russia, and Israel and Hamas, coupled with growing tension in the South China Sea, illuminate a dangerously polarizing planet. The adversaries in these disputes each broadly identify with one of the two sides of an increasingly demarcated world. It has been nearly 80 years since the world was mired in global war, and we do not expect those aligned interests and simultaneous conflicts to result in a multi-front, world war like those of the first half of the twentieth century. But persistent geopolitical uncertainty will continue to manifest violently and have near-term impacts on energy prices, investor confidence, supply chain dynamics and food security, in our view. Increased volatility emanating from this geopolitically dangerous environment is likely persist for the foreseeable future.

Ukraine: Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine resulted in broad international condemnation of Russia but also highlighted long-forming geopolitical fissures and the resultant challenges to European peace. As international sanctions, the accompanying economic pain and continuing military failure have not dissuaded Russia from its commitment to defeating Ukraine, Kyiv will likely have to redouble its efforts to shore up Western aid and materiel commitments—which have waned in the face of the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel and flagging U.S. political support. While the most likely end to the war comes in the wake of a negotiated stalemate, the conflict in Ukraine is likely to simmer for the foreseeable future.

Israel/Gaza: After Israel’s initial assault on Gaza in the wake of Hamas’ October 7 massacre of mostly Israeli civilians, international pressure has achieved some effect, and Israel has taken a more nuanced approach to its reported plan to eliminate Hamas. Israel sees this as an existential fight, however, and will likely view the decapitation of Hamas as its only path toward restoring an aura of deterrence.

That said, Israel likely understands that provoking Iran or Hezbollah or prompting popular uprisings in the West Bank may greatly complicate its military operations. Similarly, a full-scale invasion with seemingly indiscriminate civilian deaths would likely jeopardize the Abraham Accords and other nascent efforts to build stability in the region. The war has had a limited impact on energy markets to date. However, the conflict and potential for an accompanying escalation of regional instability could obviously have a deleterious effect on oil production, transportation and costs.

That said, we expect the conflict to remain contained. Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah signaled in early November that Hezbollah and other Palestinian entities operate independently of Iran—a likely effort to provide Iran maneuverability and, further, to suggest that Tehran is not likely prepared to save Hamas at the expense of its more valuable proxy, Hezbollah. As such, Israel may have some room to proceed at a pace of its own choosing, mindful of a growing international call for humanitarian caution. Somewhat paradoxically, with Israel forces’ entry into Gaza City, the air campaign is expected to also slow down.

U.S.-China tensions: Tensions between the U.S. and China over Taiwan as well as the South China Sea have increased in the last couple of years. The recent Xi-Biden meeting—while positive— marks a tactical pause in the U.S.-China strategic competition rather than any change in the fundamental relationship. Both countries desire a period of stability for different reasons: the U.S. is preoccupied with two wars in Ukraine and in the Middle East, while Xi is faced with domestic economic challenges.

We assume tensions will persist as both the U.S. and China maintain a more assertive foreign policy stance, and the relationship hardens in a variety of domains, including national and regional security, technology, economics and trade. We expect that the foundational technologies that are essential to both U.S. competitiveness and to U.S. military strength will be subject to greater protection by a multitude of tools, not just export controls, and China will respond with its own countermeasures.

For Taiwan, our baseline assumes that we are already moving up the escalation ladder, and there are substantial economic disruptions that can occur below the threshold of hot conflict.6 Incremental steps can lead to big change over time, as Beijing seeks to redefine the status quo in its near-abroad. In the meantime, Chinese interception of U.S. (and allied) aircraft in the South China Sea will remain an ongoing concern, given the risk of miscalculation and accidents.

Risk 5: Election Risk 2024 Creates Policy Uncertainty

Although election risk constitutes a type of geopolitical risk, the election risks in the U.S., Europe and Asia are significant enough to merit their own discussion.

The U.S. presidential election will take place in November 2024, so that most policy changes will take place in 2025, although some risks may clarify as we near the election. The current expectations are for a rematch of the 2020 election between Presidents Biden and Trump. There is no clear frontrunner between the two, with prediction markets showing a close race.7 The main policy risk is the re-election of President Trump: a second Biden term would be expected to continue the current policies, while a second Trump administration is likely to change or reverse key Biden administration initiatives. The main source of risk is in the area of trade and foreign policy, which are largely controlled by the Executive Branch. President Biden has attempted to pursue a mix of isolationism (via industrial policy initiatives) and alliances with both Asian and European partners. A second President Trump term is likely to revert to the more strongly isolationist policies of his first administration, reducing emphasis on alliances meant to isolate China and Russia (including reduced U.S. support for Ukraine) and building on policies meant to isolate the U.S.

The election season could trigger bipartisan rhetoric against China, requiring the Biden administration to maintain its assertive stance. A second Trump presidency would lead to a shift in the engagement framework that has been crafted under the Biden White House, leading to less space for dialogue and cooperation, and more economic and technology decoupling.

A secondary source of risk would be in climate change-related policy. Some parts of the policy are likely to remain, such as the three industrial policy acts. However, climate change regulations are likely to be modified to the extent possible by executive powers, particularly as they pertain to national security and near-term energy independence concerns.

Europe faces numerous elections in 2024, including general elections in Austria, and regional elections in Germany and Spain. While MIM’s base case is that the center ground will generally hold in upcoming polls, the recent success of far-right parties in Italy (with the election of Giorgia Meloni of the right-wing Brothers of Italy party as PM in 2022) and success of the rightwing, anti-immigration Freedom Party in Dutch elections in late-2023 raise the risk of a swing to populist parties. Such a turn at the European Parliament election could strain the EU’s ability to reach consensus on multiple issues, including around its ongoing support for Ukraine and completing reforms to the bloc’s financial framework and voting system that will be needed for it to successfully absorb future member states in the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

Outside of the EU, the UK looks likely to hold a general election sometime in 2024, potentially as soon as the spring (they must be held before January 2025, with timing at the discretion of the government). A change of government to the opposition Labour Party looks highly likely after 14 years of Conservative rule. However, with the Labour Party having moved firmly to the center-left political ground under its current leader, Sir Keir Starmer, the risk of fundamental policy uncertainty has lessened. Labour would also likely seek to further improve the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU, although there is no expectation that the UK will rejoin the EU Customs Union or Single Market anytime soon.

Finally, Taiwan’s presidential election in January will test the U.S.-China bilateral relationship, as a victory by the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan would likely lead to more Chinesemilitary coercion.

Endnotes

1 Source: Fitch Ratings

2 Source: CBO

3 Source: Institute for Supply Management, Reports on Business, Nov 2022-Nov 2023

4 Source: Discussion with Strategas, September 28, 2023

5 As of most recently available data (August 2023) from energy.gov and eia.gov.

6 MIM China Deep Dive Conference 2023, “The Taiwan Factor,” remarks by Reva Goujon, Director, Rhodium Group, November16, 2023.

7 E.g. Predictit.org gave odds of a 39% probability of a Trump win and a 38% Biden win as of November 20, 2023.

Disclaimer

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors. This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as of the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

All investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results. Property is a specialist sector that may be less liquid and produce more volatile performance than an investment in other investment sectors. The value of capital and income will fluctuate as property values and rental income rise and fall. The valuation of property is generally a matter of the valuers’ opinion rather than fact. The amount raised when a property is sold may be less than the valuation. Furthermore, certain investments in mortgages, real estate or non-publicly traded securities and private debt instruments have a limited number of potential purchasers and sellers. This factor may have the effect of limiting the availability of these investments for purchase and may also limit the ability to sell such investments at their fair market value in response to changes in the economy or the financial markets

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address 1 Angel Lane, 8th Floor, London, EC4R 3AB, United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) under the registration entry Director General of the Kanto Local Finance Bureau (FIBO) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong S.A.R.: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”). MIAL is licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission for Type 1 (dealing in securities), Type 4 (advising on securities) and Type 9 (asset management) regulated activities.

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

MIMEL: For investors in the EEA, this document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited (“MIMEL”), authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland (registered number: C451684), registered address 20 on Hatch, Lower Hatch Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. This document is approved by MIMEL as marketing communications for the purposes of the EU Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments (“MiFID II”). Where MIMEL does not have an applicable cross-border licence, this document is only intended for, and may only be distributed on request to, investors in the EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under MiFID II, as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction. The investment strategies described herein are directly managed by delegate investment manager affiliates of MIMEL. Unless otherwise stated, none of the authors of this article, interviewees or referenced individuals are directly contracted with MIMEL or are regulated in Ireland. Unless otherwise stated, any industry awards referenced herein relate to the awards of affiliates of MIMEL and not to awards of MIMEL.

1 As of March 31, 2023, subsidiaries of MetLife, Inc. that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/or unaffiliated/third party investors include Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), MIM I LLC, MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited, Affirmative Investment Management Partners Limited and Raven Capital Management LLC