A Precarious Fiscal Situation

The United States faces a challenging fiscal outlook. A rising primary deficit (the deficit excluding interest payments) and rising interest rates are projected to push federal debt held by the public to the highest levels in the country’s history, easily surpassing levels reached during World War II.

Even if discretionary spending is reduced, fiscal pressure may remain high in the longer term as an aging population and rising healthcare costs increase spending in “mandatory” programs like Social Security and Medicare.

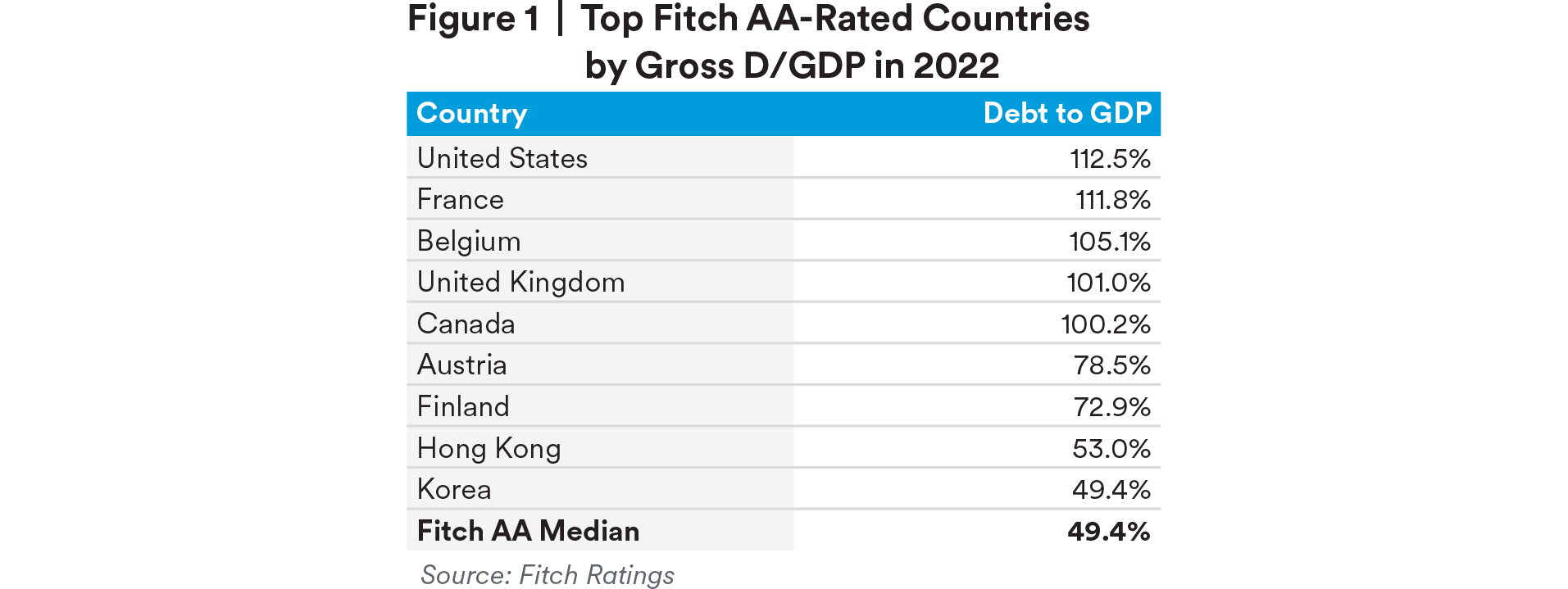

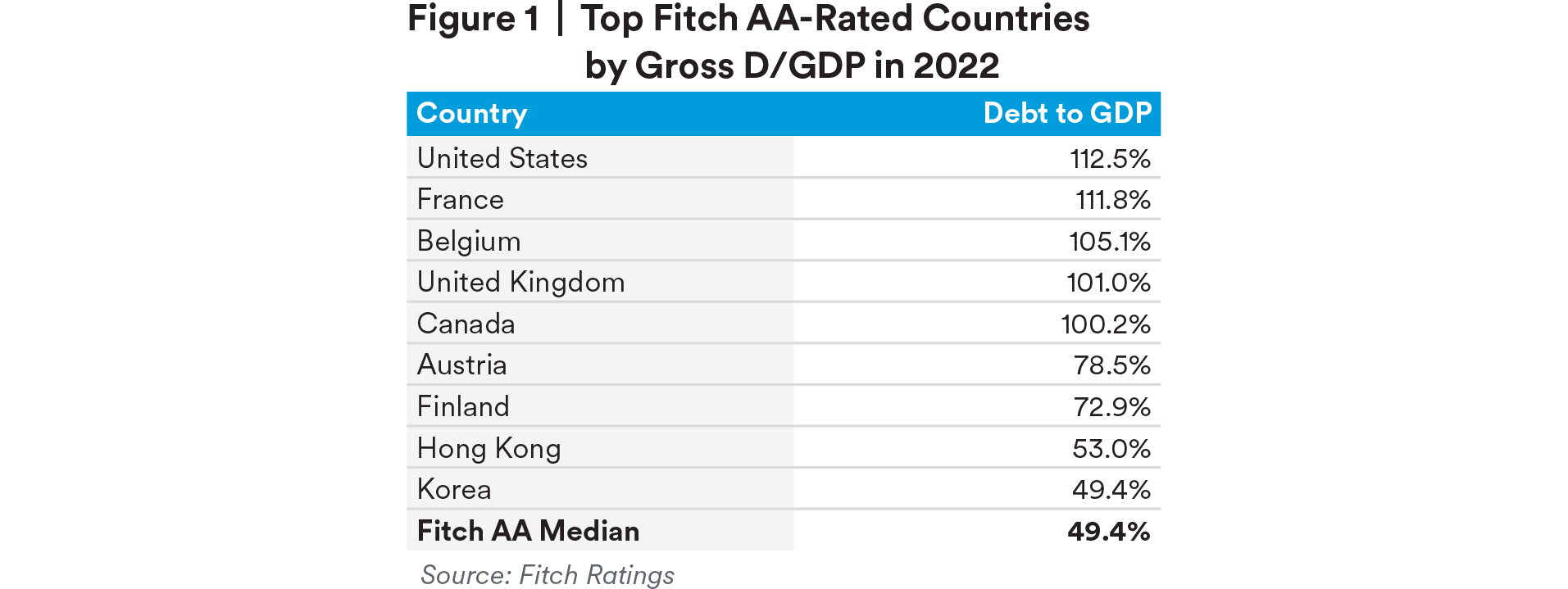

Between the years 1940 and 2007, Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data show the U.S. had an average primary deficit of 1.1% and an average total deficit of 2.9%. Since 2008, these have ballooned: the primary deficit has averaged 4.7% (3.6% if two pandemic years are excluded), and the total deficit averaged 6.2% (5.1% excluding pandemic). The country’s total debt-to-GDP reached 113% in 2022. While Moody’s still rates the U.S. as AAA, Fitch recently downgraded the U.S. to AA and even then, the median Fitch AA-rated country had a debt-to-GDP ratio of just 49% (Table 1).

While these trends are a risk for the U.S. economy, especially given increased scrutiny over the government’s budgeting process, they also have an impact on the global financial system, given the international role of the U.S. dollar and, relatedly, the Treasury market. A loss of confidence in the U.S. credit worthiness could impact investor preferences for U.S. Treasuries, leading to higher borrowing costs for the U.S. government and the private sector, as well as for other countries that rely on the U.S. dollar for trade and financing. Moreover, further downgrades could accelerate the diversification of central bank reserves and undermine the status of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, reducing the demand for U.S. assets and increasing exchange rate and interest rate volatility. Ever rising debt issuance could also crowd out other investments, and investors may demand higher yields to absorb the growing supply of U.S. Treasuries. These effects could in turn exacerbate the economic and fiscal challenges facing the country, creating a spiral that may be hard to control.

Stable Revenue, Growing Outlays

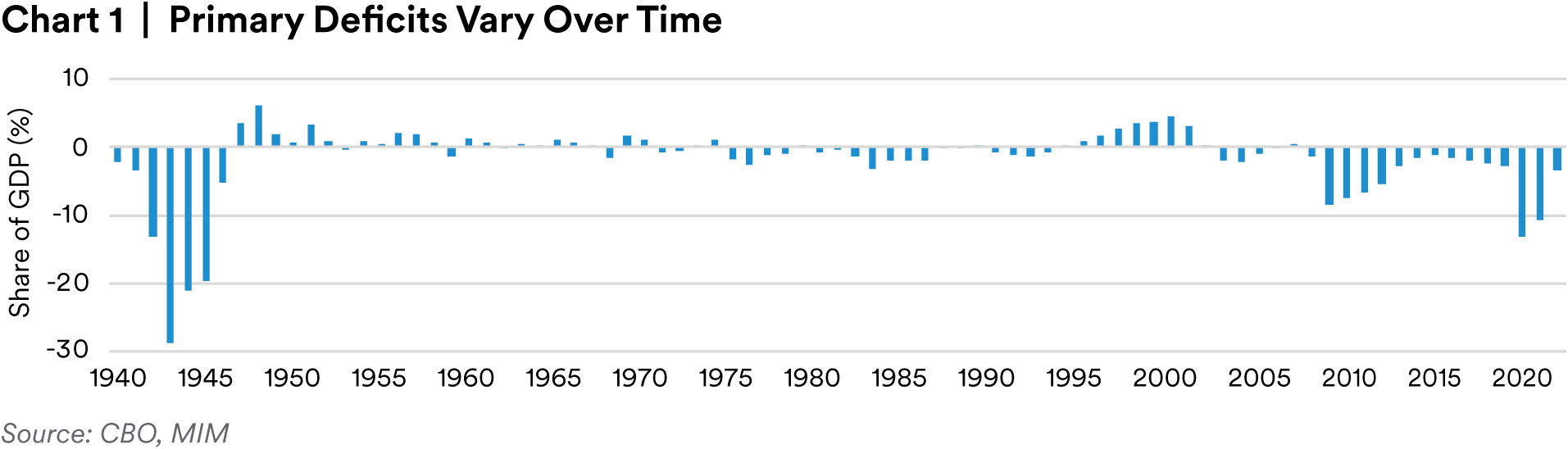

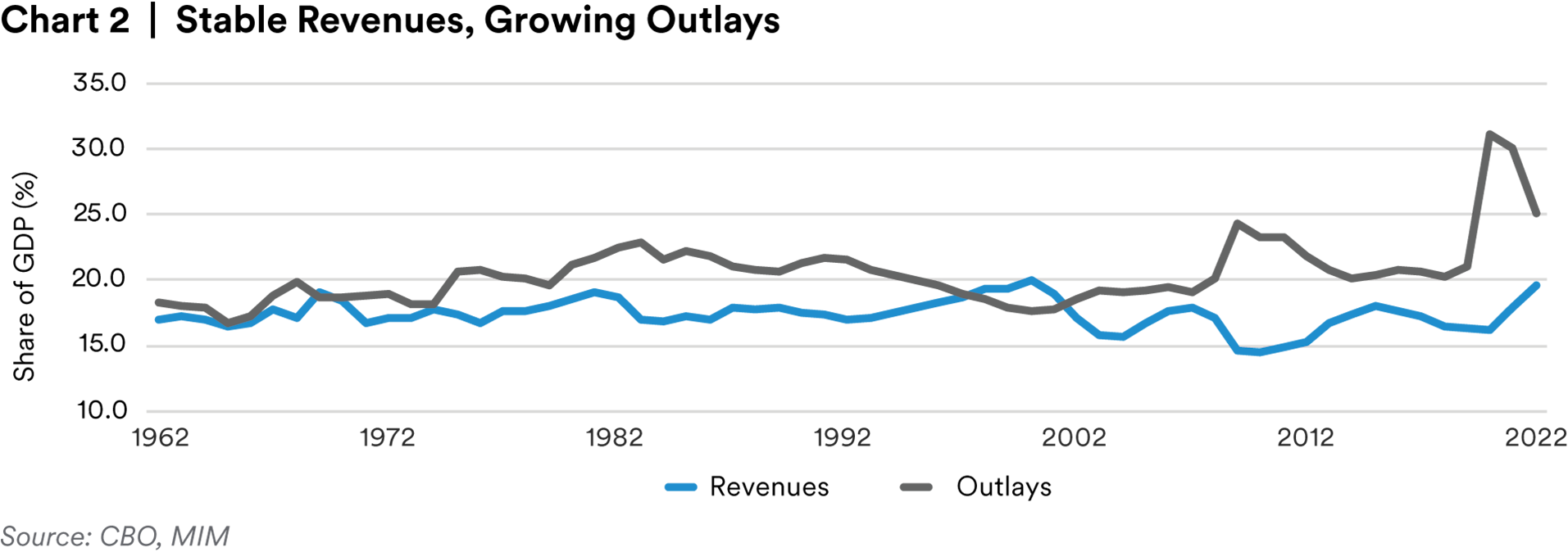

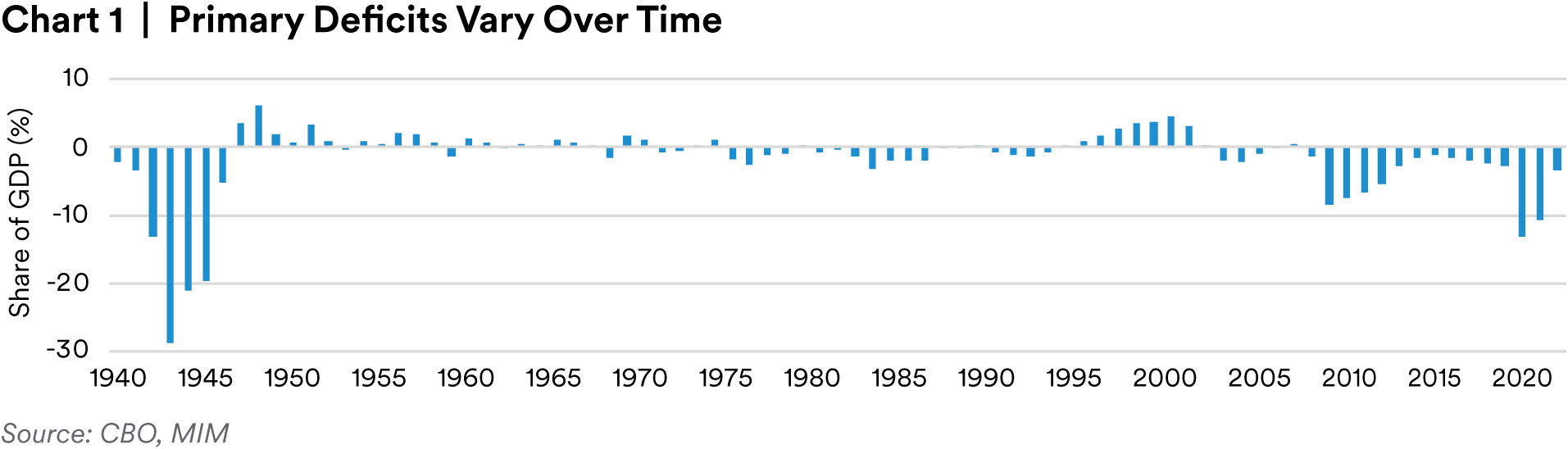

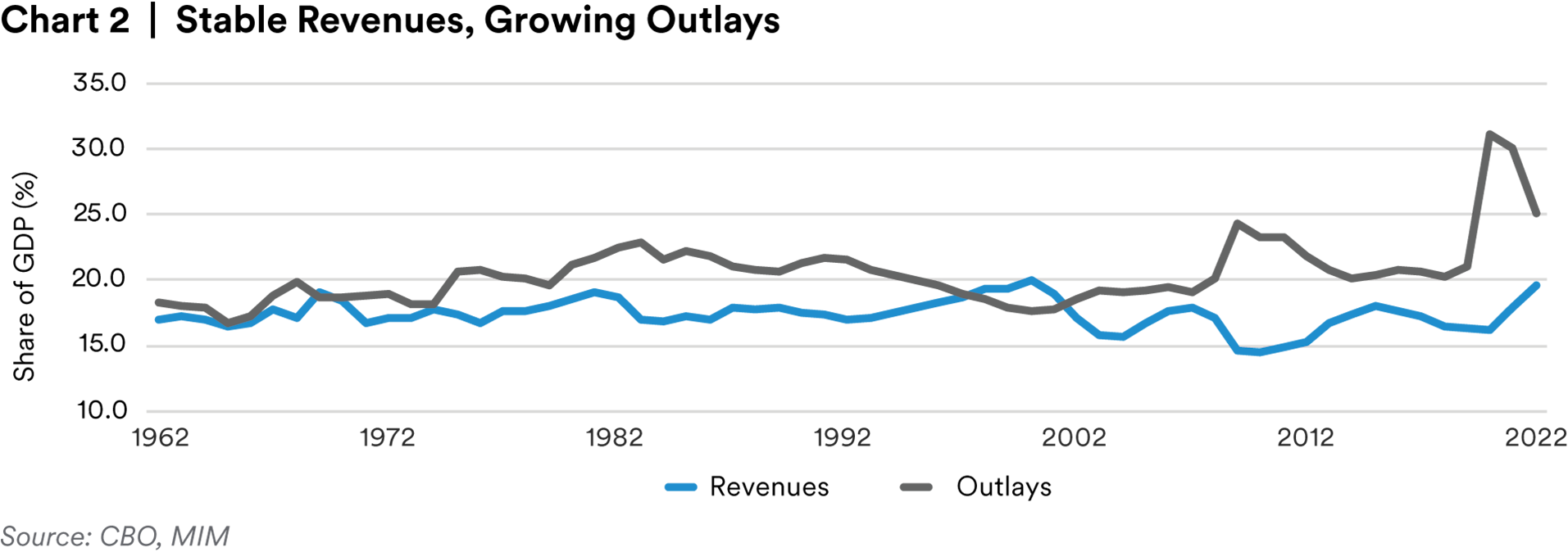

The U.S.’ primary deficit fluctuates significantly from year to year (Chart 1), but this variation obscures a core point that, over time, revenues as a share of nominal GDP have stayed relatively stable while outlays have fluctuated (i.e., increased).

CBO data show that from 1963 to 2022, government revenue averaged 17.4% of nominal GDP, witha standard deviation of just 1.1%. Revenue does decline in a recession; it fell to 14.6% in 2009. It also increases in good times, reaching a peak of 20% of GDP in the late 1990s (Chart 2). But the range of revenue outcomes is narrow, and the variance is low. Meanwhile, total government outlays increased from just over 18% of GDP in 1962 to just over 25% at the end of 2022 (Chart 2).

What About the Future?

The future path of the public debt (“debt”) should depend on two main drivers: real GDP growth, via productivity increases, and the deficit, via government spending decisions. Using annual data from 1963 to 2019, our model finds that that assuming no growth and no deficit, debt would decrease by 1.4pp every year (Source: BEA, CBO, MIM). Each percentage point of real GDP growth would decrease the debt a further 0.3pp. Government policy is a bigger driver, with each point ofsurplus decreasing the debt an additional 1.1pp each year.

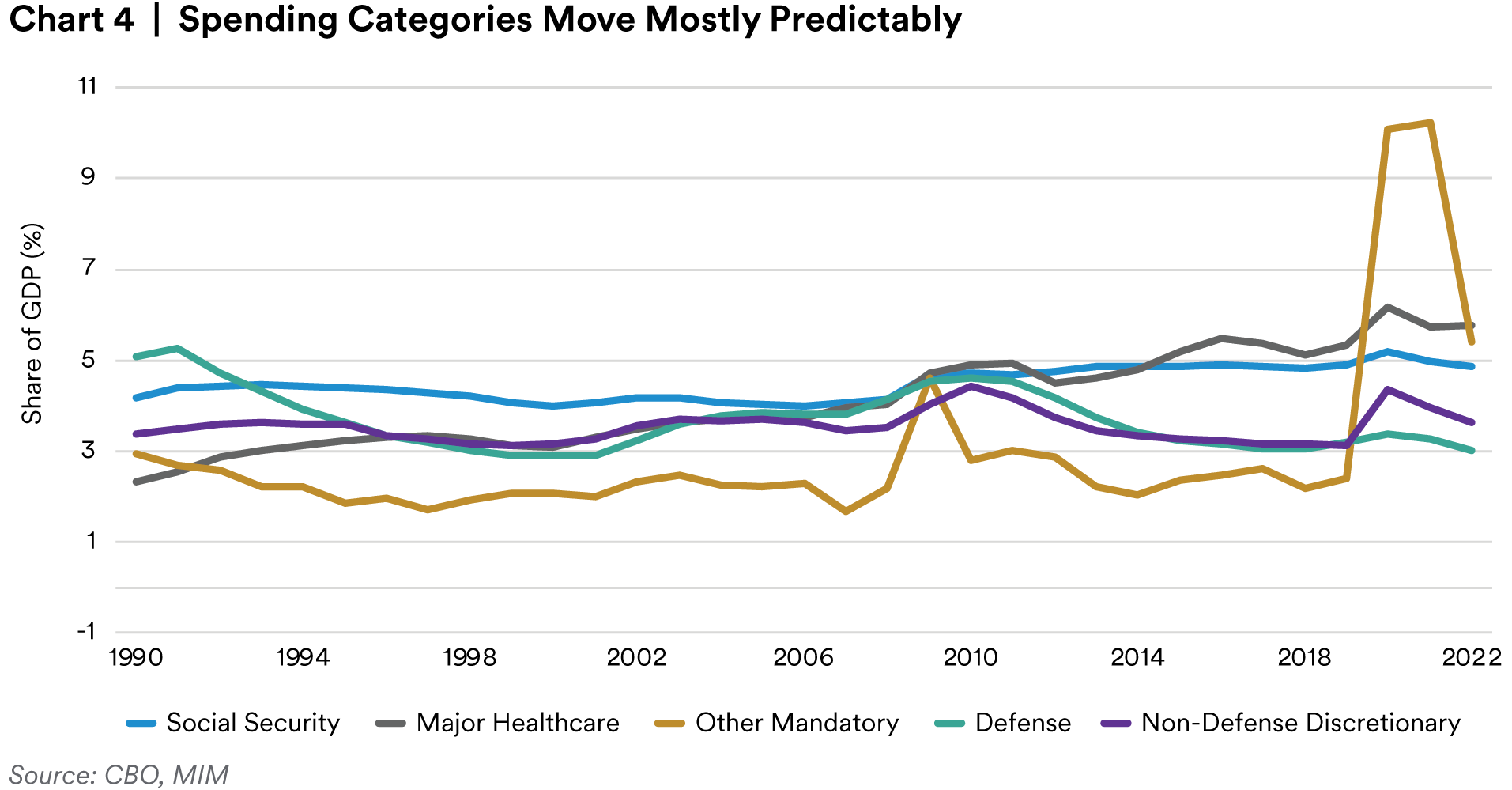

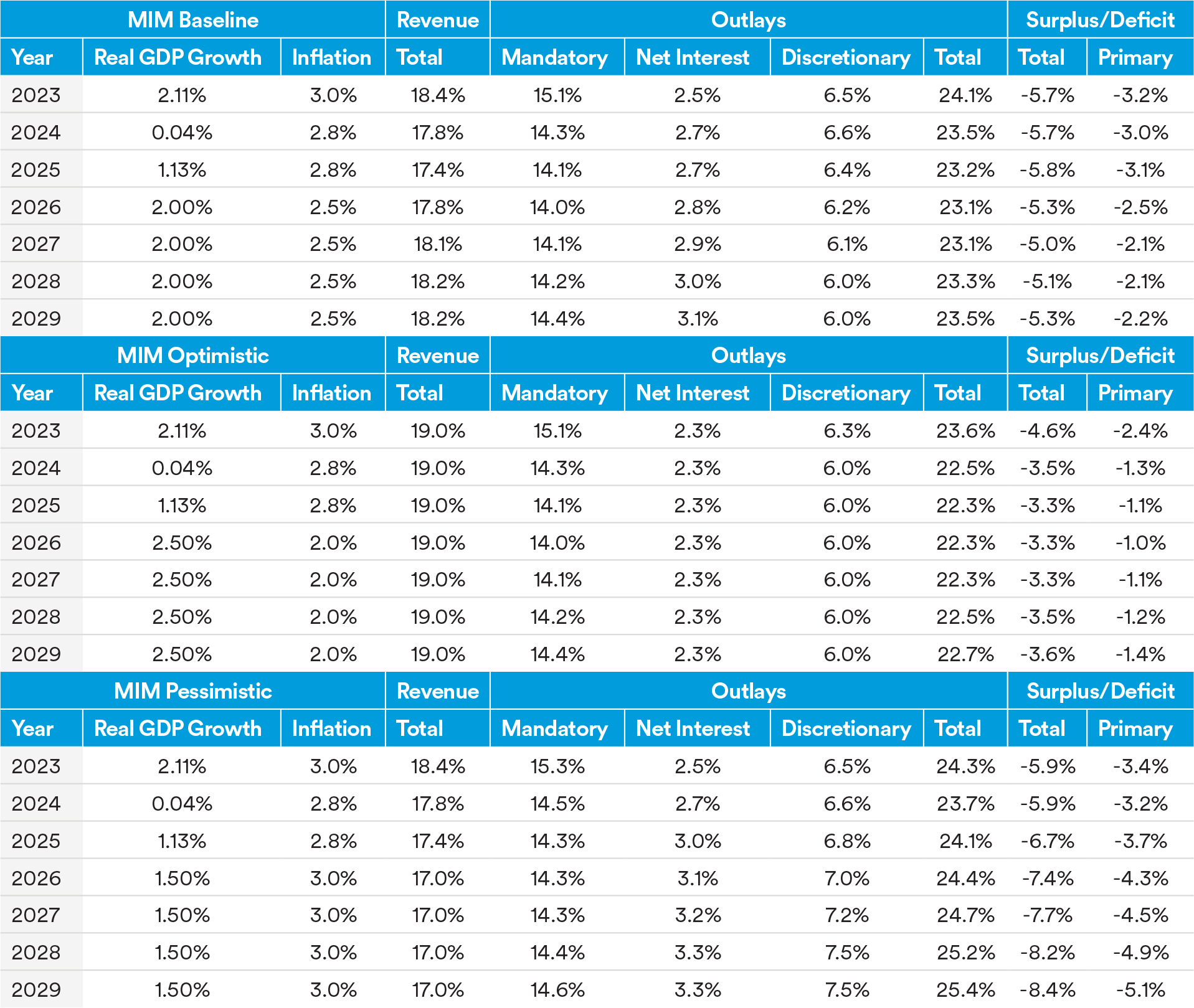

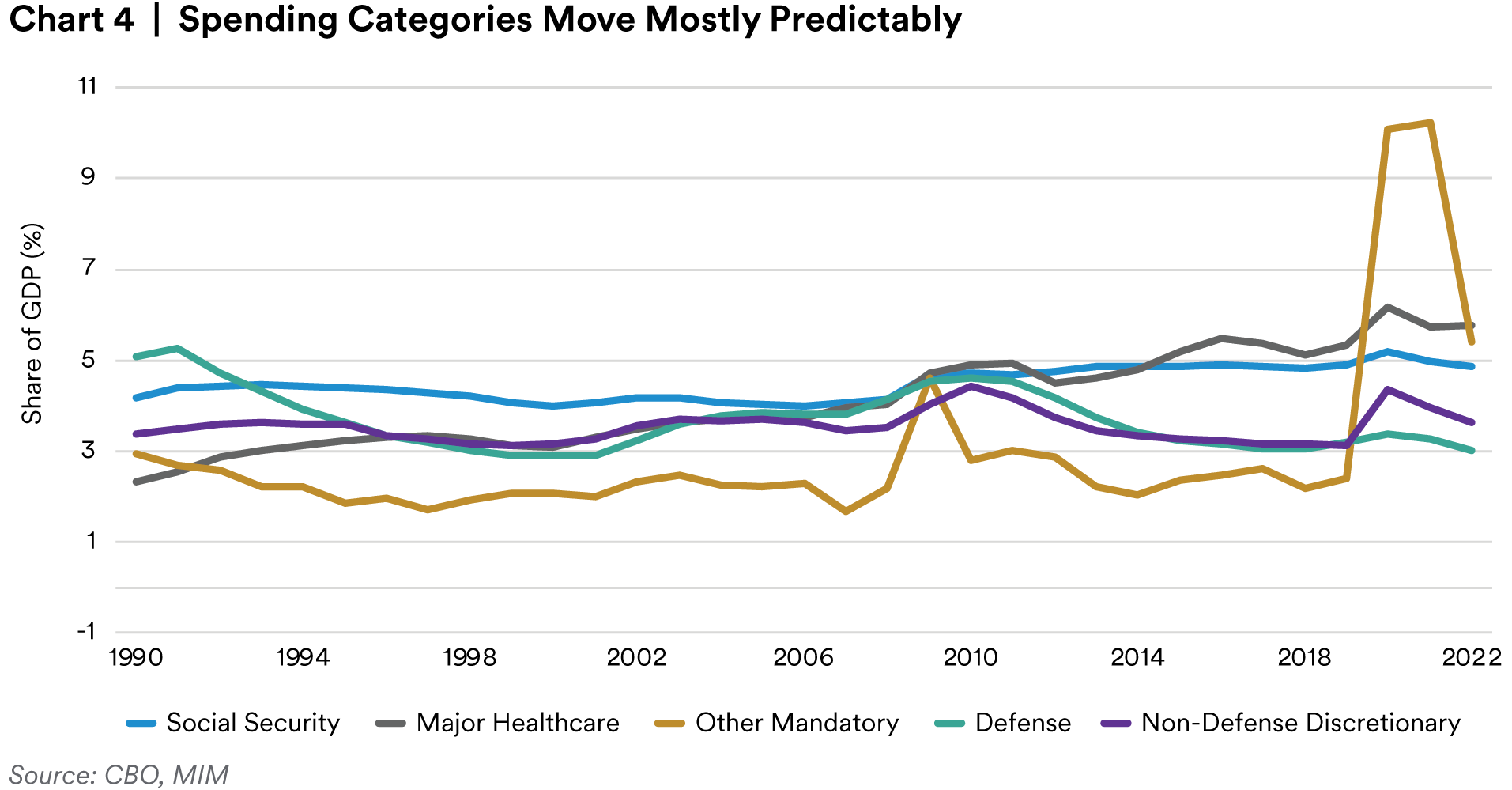

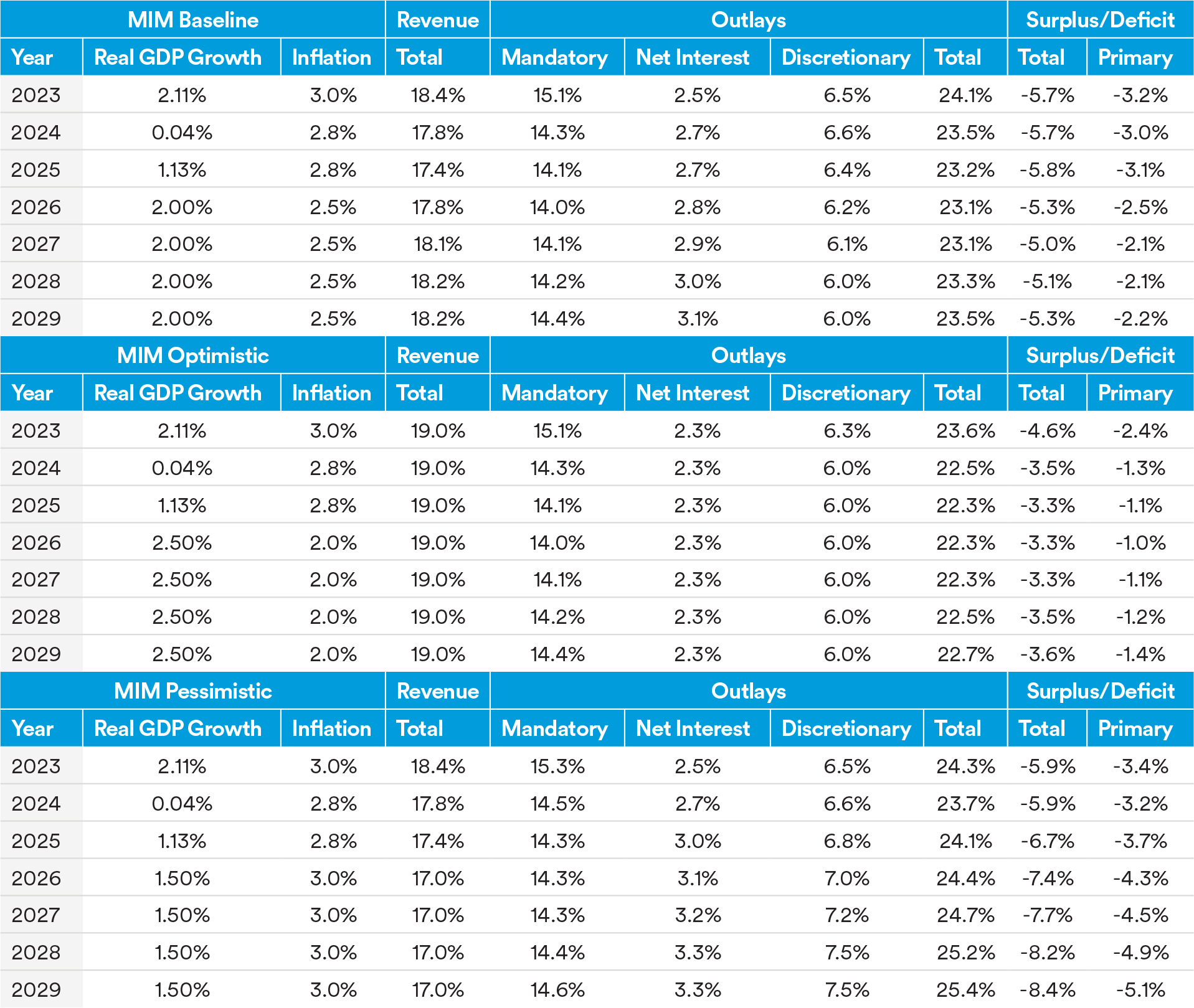

The relative stability of government spending as a share of GDP over time (Chart 4) extends to the components of revenues and outlays (e.g., non-defense discretionary spending and healthcare spending) and allows us to construct reasonable assumptions of the deficit over time, barring extraordinary circumstances. Combining these assumptions with MIM’s GDP and inflationfore casts allows us to construct scenarios depicting the potential trajectories of U.S. debt over the next few years.

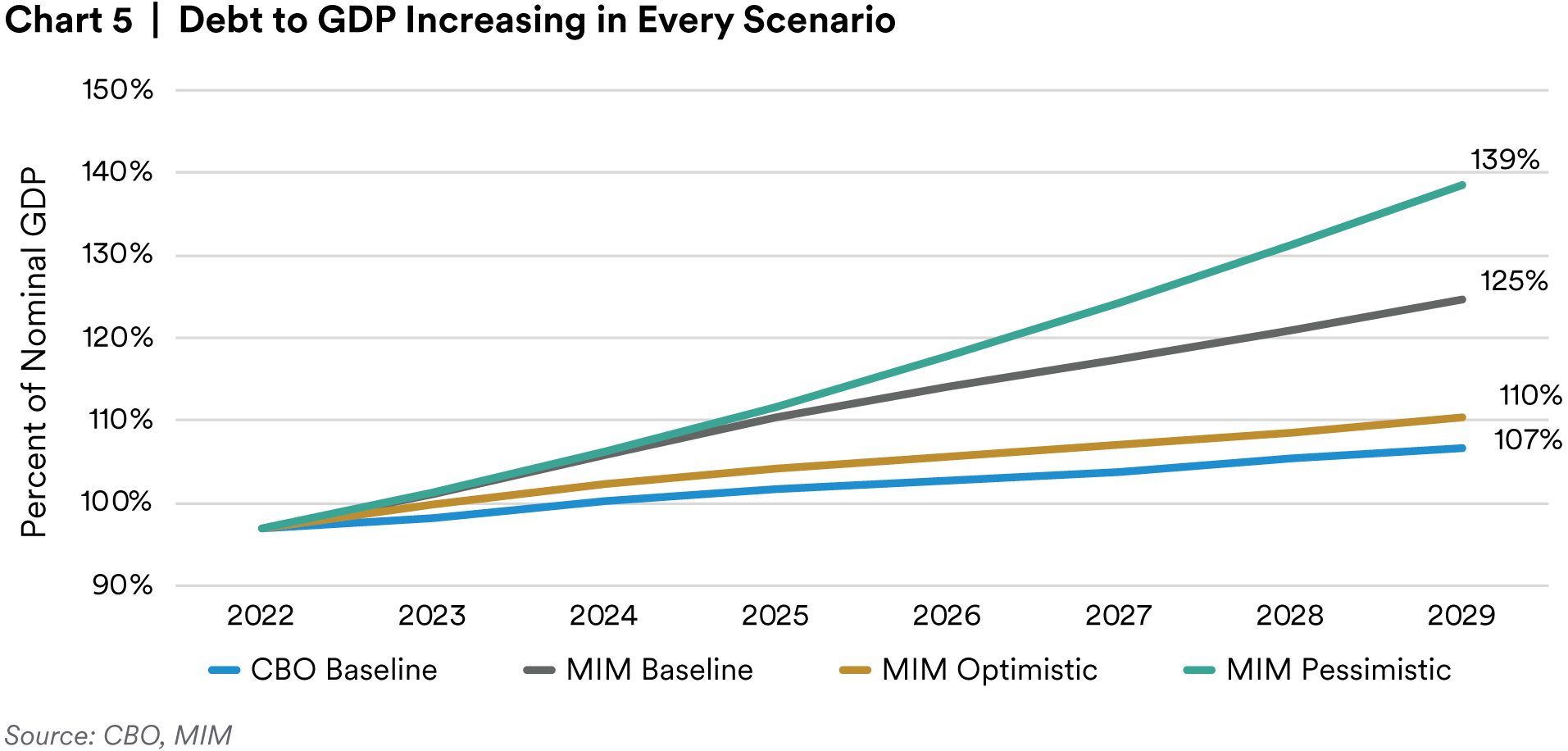

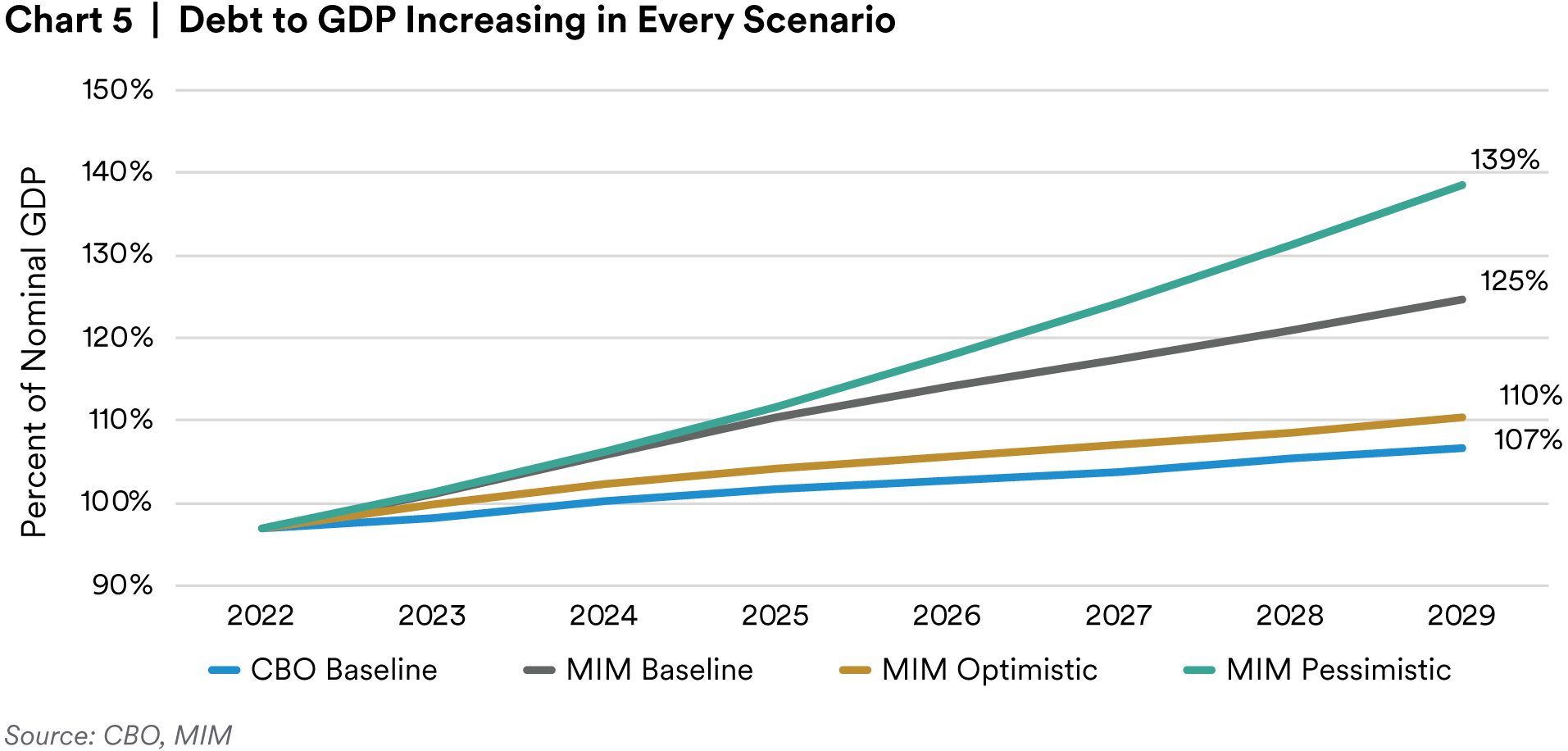

In all of our scenarios (see Appendix for key assumptions), and in the CBO’s baseline included for comparison, debt as a share of GDP increases over the next six years. In our most optimistic scenario, we assume increased government revenue, decreased net interest outlays, and decreased discretionary spending. In the pessimistic scenario, we assume the opposite in all three variables, along with a slight increase in other mandatory spending. 1 Increased defense spending, which is considered discretionary, 2 would be somewhat captured by this scenario. Every scenario makes similar assumptions about healthcare and Social Security, as these are less flexible. Healthcare expenses are predicted to increase 0.3pp to 5.9% of GDP by 2029, and Social Security expenses are projected to increase by 1pp to 5.7% of GDP by 2029.

It is important to note that our baseline estimate and the CBO’s baseline estimate use different underlying macroeconomic assumptions as well as a different approach in estimating the changein debt. MIM’s explicit recession forecasted in the first half of 2024 sets the level of debt higherat the outset, but then our optimistic scenario grows at a similar pace to the CBO’s baseline. The CBO’s own scenario analysis around its baseline assumptions have debt reaching 103% to 118% by 2029.

While debt-to-GDP is the most conventional metric for measuring sovereign leverage, the interest-to-revenue ratio is also used by ratings agencies because it shows the impact debt ishaving from a cash flow perspective. WorldBank data show that in 2021 the U.S. had an interest to revenue of 13.3%, far higher than the OECD average of 3.2% and more in line with a BBB-rated emerging market credit rather thanthat of an AA-rated developed market. Our model predicts this to further deteriorate to 17% by 2029 in the baseline scenario, exacerbated by higher percentages of short-term debt andmore debt rolling over at prevailing higher rates.

More Debt is Coming, but How Much?

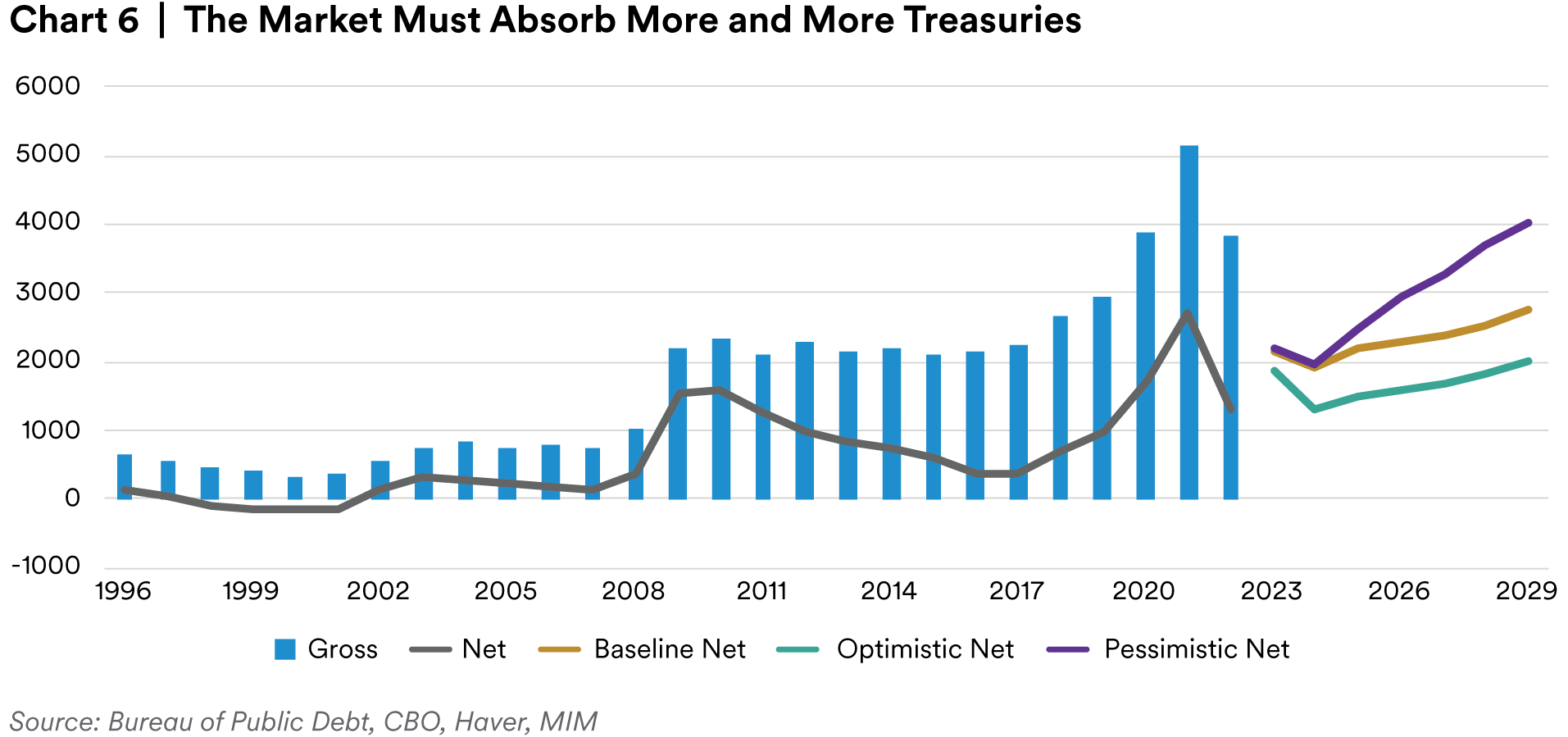

Our focus is on debt held by the public (i.e., excluding intra-governmental debt like that owed to the Social Security Administration (SSA)), because this issuance is ultimately what must be absorbed at auctions, with more direct implications for the Treasury market.

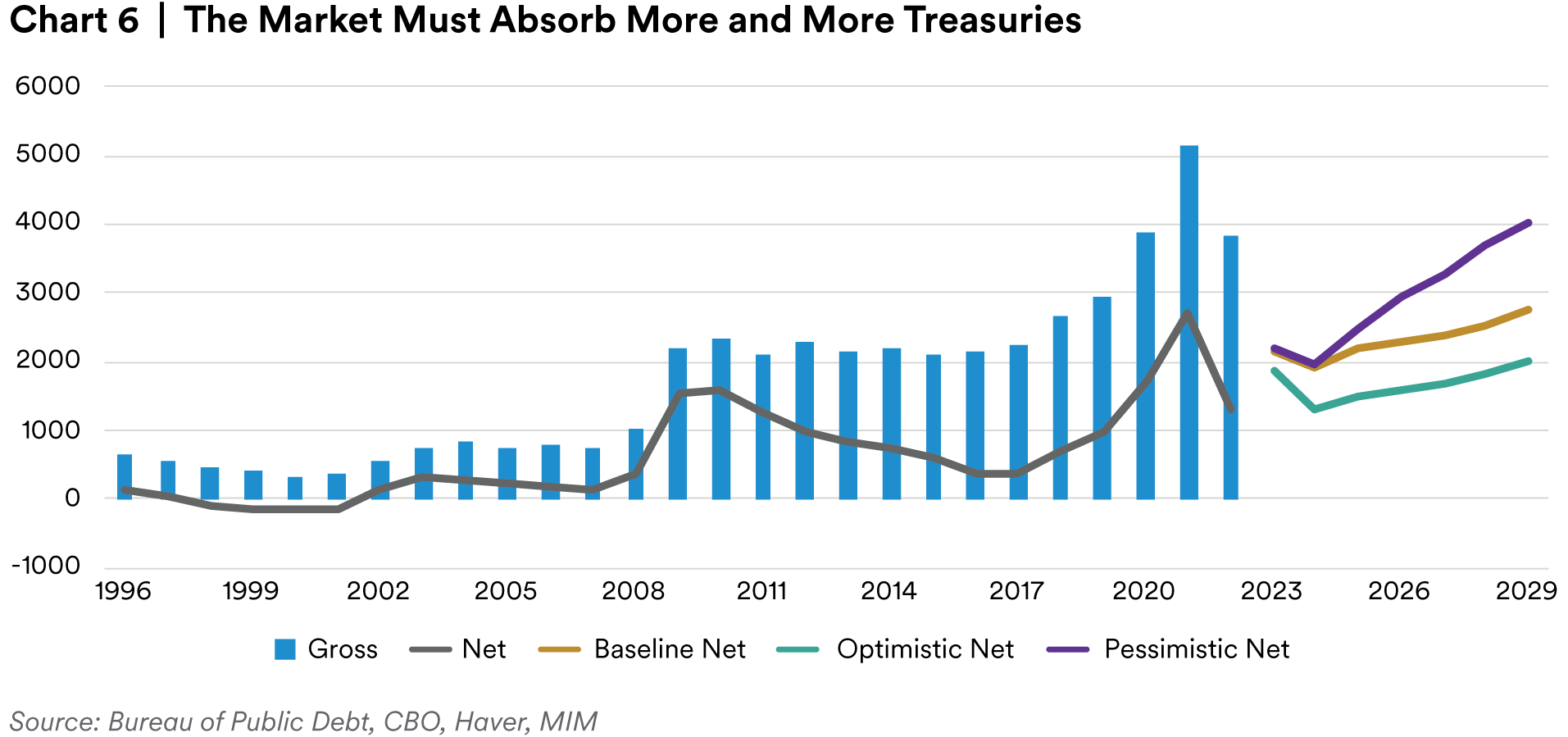

By the end of 2022, the CBO reported that this debt was around $24.6 trillion. In our baseline scenario, we project a net average annual issuance (i.e., gross issuance excluding maturing securities and bills) of roughly $2.5 trillion, resulting in a debt level of over $42 trillion by 2029. In our optimistic scenario, average issuance of $1.9 trillion would result in a debt level of $38 trillion.

The pessimistic scenario yields about $3.2 trillion in average annual net issuance and a debt level of $47 trillion by 2029.

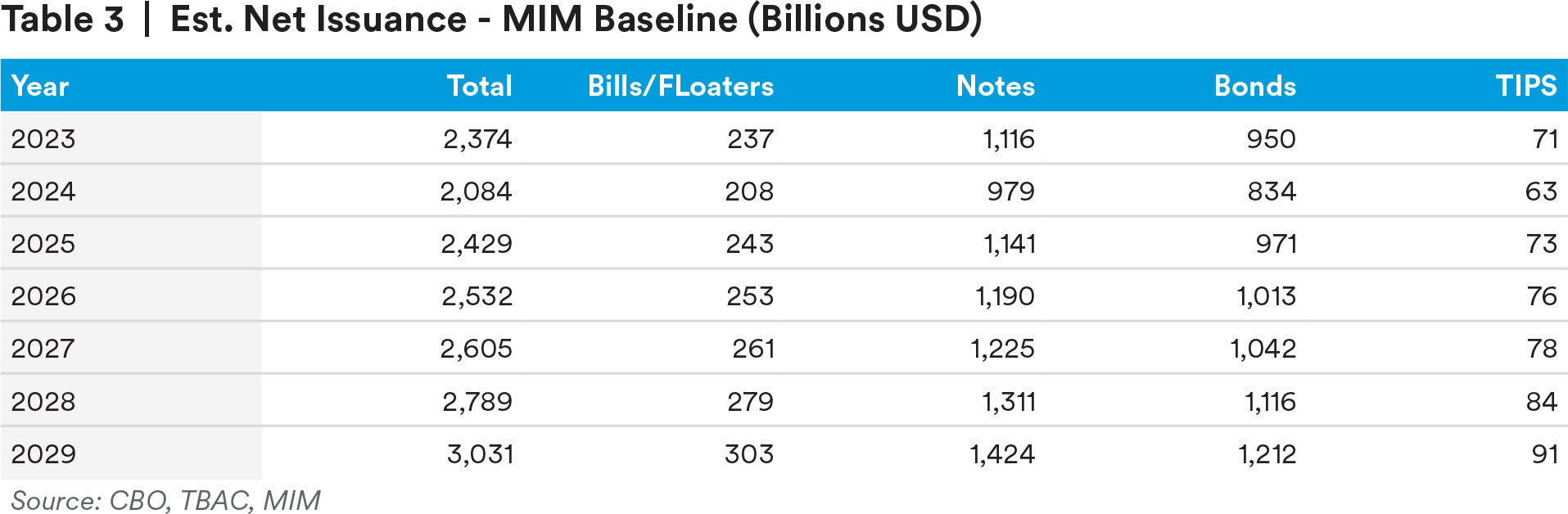

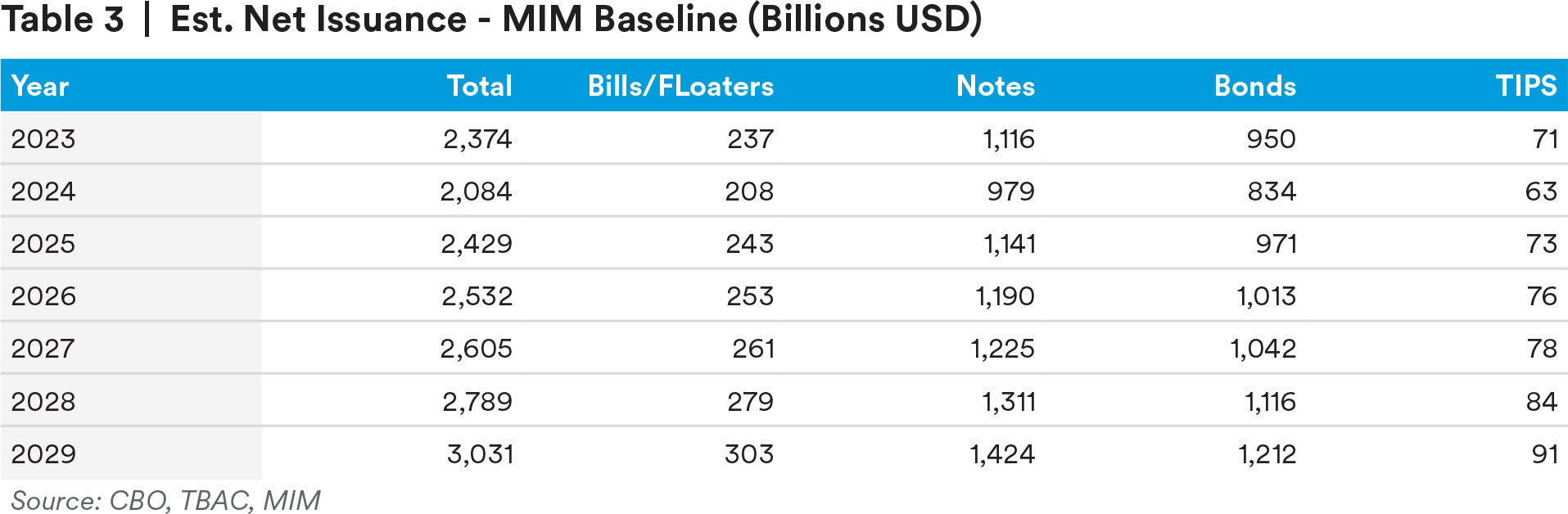

Using previous work done by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) on Treasury issuance patterns, we can use an estimate of the “steady state” maturity composition of debt to get an idea of how new net issuance will be distributed among the different types of government securities (Table 3).3

An additional point is that debt held by the Federal Reserve is included in the public debt, but this debt is technically not available to the public. Therefore, the Fed’s balance sheet normalization will put further upwards pressure on the supply of debt available to investors. In this case, the Treasury will also end up paying more interest as the Fed will no longer be remitting its excess interest income back to the Treasury as it did in the past (the Treasury effectively paid a 0% interest rate on those holdings).

In short, the market must be prepared to absorb an increasing number of Treasury notes and bonds. By way of comparison, between 1996 and 2019, Federal Reserve data show the average annual net issuance was just $478 billion. Moreover, in past years where net issuance was greater than $1 trillion (2009-2011, 2020), the Fed was an active buyer of securities, leaving the true net amount of bonds absorbed by the market closer to the historical average.

What Can be Done?

In order to stabilize the debt trajectory, an aggressive and sustained fiscal adjustment is needed, to the tune of 3-4% of GDP, according to our model. While that number may appear small, it is drastic. 3% of GDP amounts to 50% of the government’s discretionary spending, or the entirety of defense spending in 2022. It is roughly half of the annual expense of all major healthcare programs combined, or equivalent to 60% of 2022’s social security expenditures. Some of the gap could also be made up by revenue increases, but 2022’s revenues of 19.6% of GDP were close to the highest seen since the 1960s. Whatever the combination, policymakers will have to negotiate a very delicate situation if they are to make a deliberate effort to change the U.S.’ debt trajectory.

If a spending cut of 3% of GDP coincides with a productivity boom (real GDP growth of 3%), very similar to the situation in the 1990s, then we predict a slight decline in debt-to-GDP to the tune of 0.1pp annually. But the spending reductions are crucial; we do not expect strong growth (within reason) alone to decrease debt-to-GDP.

Complex Challenges Ahead

We expect the U.S. debt burden to increasing materially in all plausible scenarios . As time passes, the challenges become more complex. For example, in 2021 the Social Security Trust Fund began redeeming excess reserves to fill a funding gap. As the gap grows, the government will have to cut spending elsewhere to fund Social Security’s redemptions, or issue even more bonds to the public.

But the Trust Fund’s excess reserves are estimated to run out in the 2030s, and the Congressional Research Service projects annual contributions will only be able to fund 80% of Social Security obligations. Within the next decade, the U.S. government will have to cut benefits or find alternative solutions (potentially using more debt) to fund the 20% shortfall.

Regardless of the precise level of debt reached in the next decade, the one thing that can be said with relative certainty is that the markets will have to wrestle with an increased issuance of Treasury bonds as the government tries to finance its obligations. More issuance could put upward pressure on interest rates, dampening economic activity and raising inflation expectations.

Meanwhile, the current political landscape does not seem amenable to the tough fiscal adjustment required to avoid this path.

Worse, if investors lose confidence in the U.S. fiscal position, markets may begin to treat Treasuries less as an exceptional asset and more as one of many high quality, low risk assets. Ratings pressure may increase as well, as a loss of confidence is likely to undermine the U.S.’ last remaining AAA rating (Moody’s), or even push the country’s debt towards a single A rating, similar to Japan.

Appendix – Key Scenario Assumptions

All revenues, outlays, and deficits expressed as a percentage of nominal GDP.

Endnotes

1 “Other” mandatory spending includes tax credits and programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, unemployment insurance, the earned income tax credit, and the child tax credit.

2 Non-defense discretionary spending includes areas such as education, transportation, veterans’ healthcare, and homeland security.

3 This assumes the current funding strategy remains in place. While it is reasonable to expect a change in the funding strategy in the medium- or long-term, the exercise gives insight into the breakdown of issuances in the near term.

Disclaimer

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors. This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as of the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

All investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results. Property is a specialist sector that may be less liquid and produce more volatile performance than an investment in other investment sectors. The value of capital and income will fluctuate as property values and rental income rise and fall. The valuation of property is generally a matter of the valuers’ opinion rather than fact. The amount raised when a property is sold may be less than the valuation. Furthermore, certain investments in mortgages, real estate or non-publicly traded securities and private debt instruments have a limited number of potential purchasers and sellers. This factor may have the effect of limiting the availability of these investments for purchase and may also limit the ability to sell such investments at their fair market value in response to changes in the economy or the financial markets

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address 1 Angel Lane, 8th Floor, London, EC4R 3AB, United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) under the registration entry Director General of the Kanto Local Finance Bureau (FIBO) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong S.A.R.: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”). MIAL is licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission for Type 1 (dealing in securities), Type 4 (advising on securities) and Type 9 (asset management) regulated activities.

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

MIMEL: For investors in the EEA, this document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited (“MIMEL”), authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland (registered number: C451684), registered address 20 on Hatch, Lower Hatch Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. This document is approved by MIMEL as marketing communications for the purposes of the EU Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments (“MiFID II”). Where MIMEL does not have an applicable cross-border licence, this document is only intended for, and may only be distributed on request to, investors in the EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under MiFID II, as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction. The investment strategies described herein are directly managed by delegate investment manager affiliates of MIMEL. Unless otherwise stated, none of the authors of this article, interviewees or referenced individuals are directly contracted with MIMEL or are regulated in Ireland. Unless otherwise stated, any industry awards referenced herein relate to the awards of affiliates of MIMEL and not to awards of MIMEL.

1 As of March 31, 2023, subsidiaries of MetLife, Inc. that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/or unaffiliated/third party investors include Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), MIM I LLC, MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited, Affirmative Investment Management Partners Limited and Raven Capital Management LLC