In our view, the property sector’s recovery is the key wild card for China’s economy next year and unless managed well under Beijing’s policy regime shift, could lead to unintended consequences. We are making a bet that policymakers will succeed in preventing a hard landing for the property sector as incremental support broadens out further in the first quarter, ensuring a gradual but modest economic recovery ahead of the all-important 20th Party Congress later next year when Xi Jinping’s leadership mandate is likely to be extended for at least two more five-year terms. Just as this year’s slowdown has been largely policy-induced, we feel so will China’s modest recovery next year.

Beijing’s reluctance to ease reflects a policy “regime shift”

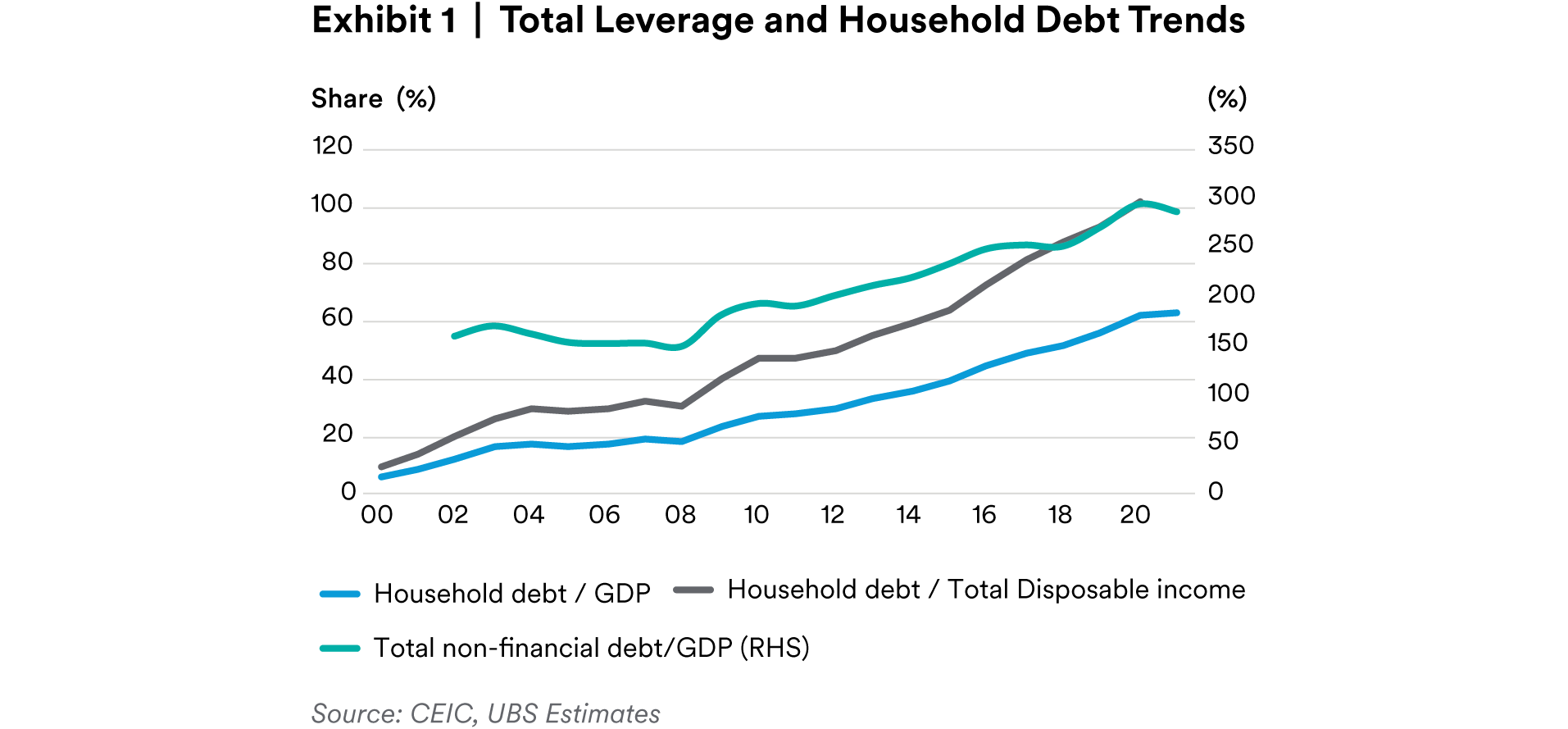

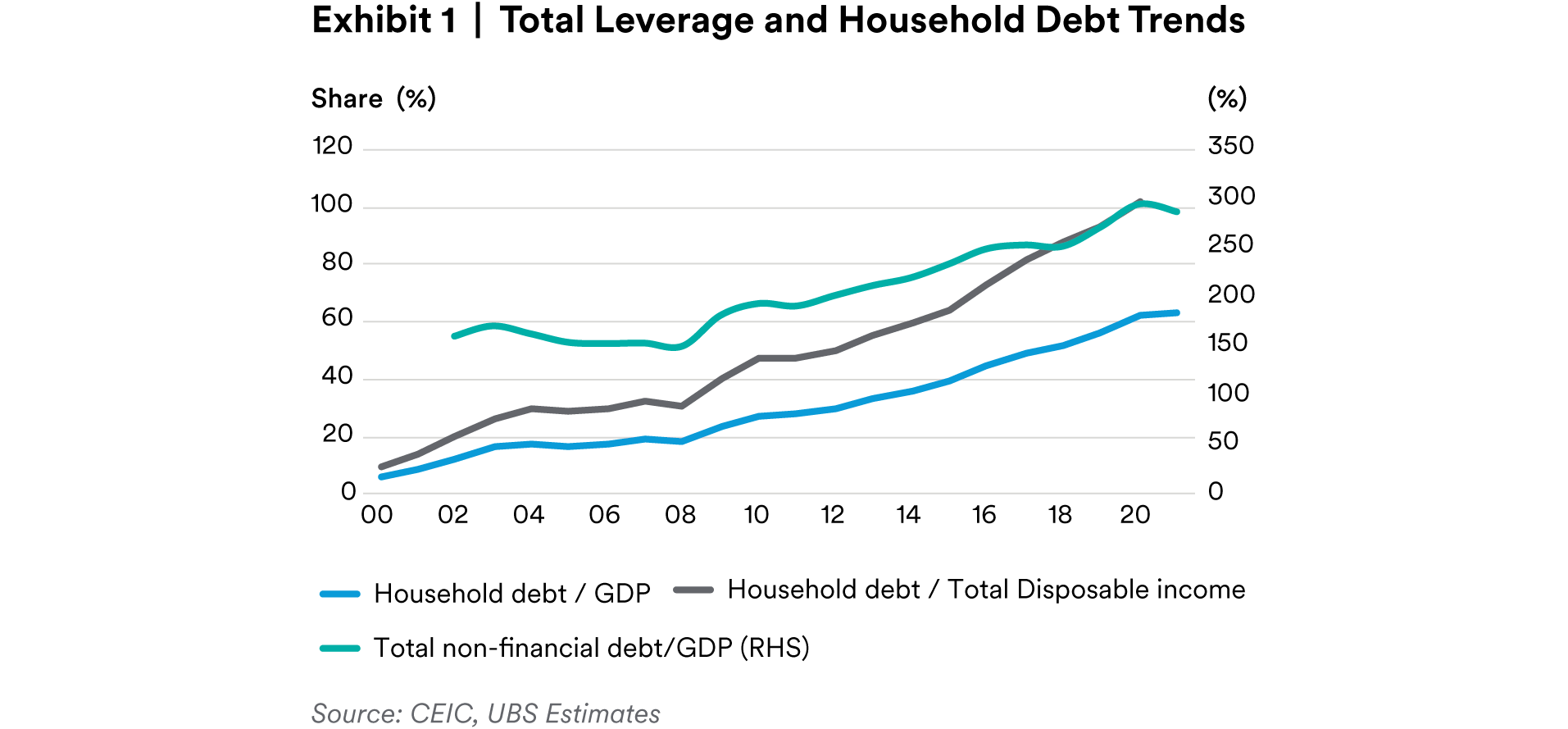

De-leveraging the economy. As is widely known, China’s growth model has been largely investment-led, creating a massive stockpile of leverage in the economy. In recent years Beijing has attempted to rein in credit growth for fear of exacerbating risks in the financial system, articulating a goal of capping total credit growth roughly in line with that of nominal GDP to prevent further increases in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The rise in leverage took another step up in 2020 as Beijing eased policy in the wake of the initial COVID-19 outbreak. In fact, last year’s increase in credit pushed China’s debt-to-GDP ratio to 296%, the highest level on record [Exhibit 1]. But by the end of 2020, credit growth had slowed as Beijing doubled down once again on its de-risking initiatives.

Better quality, more equitable growth. Since earlier this year, another layer of economic and social goals has emerged from Xi Jinping’s Common Prosperity program, which aims to achieve better quality growth, less income inequality, and improved livelihoods for households by easing the burden of housing, education, and healthcare costs. Coupled with de-risking efforts, these longer- term objectives suggest a higher tolerance for lower growth going forward as Beijing attempts to rebalance China’s growth model away from credit-driven investment and the property sector to new engines of growth including consumption and services, “greener” industries, and the technology sector.

Improving housing affordability. Within the property sector, policy has also undergone a regime-shift since 2017 when Xi Jinping stated that “housing is for living, not for speculation”. The combination of high investment and surging debt is closely related to the size and rapid growth of the property sector, and, in the last few years, regulators have tightened mortgage availability and down-payment requirements as household debt rose to record levels (Exhibit 1). In mid-2020, regulators also began targeting developers with the so-called “Three Red Lines”, aimed at capping their leverage as measured by three balance sheet metrics, which helped drive a construction boom that pushed steel production to its highest ever level.1 As elevated home prices have been a major source of economic inequality, the crackdown on developer and household leverage is consistent with Beijing’s broader de-risking campaign and Common Prosperity program, which ultimately seek to rid the sector of excesses and improve housing affordability. This theme is likely to be the centerpiece of discussions at next year’s 20th Party Congress.

Beijing’s de-leveraging campaign is here to stay. In our view, Beijing’s reluctance to ease policy more substantially year-to-date is born out of a concern that it could undermine credibility in its campaign to reduce moral hazard and de-risk the economy. Moreover, any relaxation of policy would risk igniting another property bubble, quickly unwinding Beijing’s successes to date. The policy regime shift is politically tinged as well, in that it seeks to enhance longer term growth sustainability to preserve the legitimacy and power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Common Prosperity is Xi Jinping’s response to widespread anxieties about inequality, a social ill that he wants to overcome and build his legacy on. The CCP’s ability to maintain unchallenged political control will ultimately depend on its capacity to meet what Xi says is “the people’s demand for a happier life.” In our view, the political and strategic importance of Beijing’s policy regime shift should not be underestimated.

More pain to come in the property sector

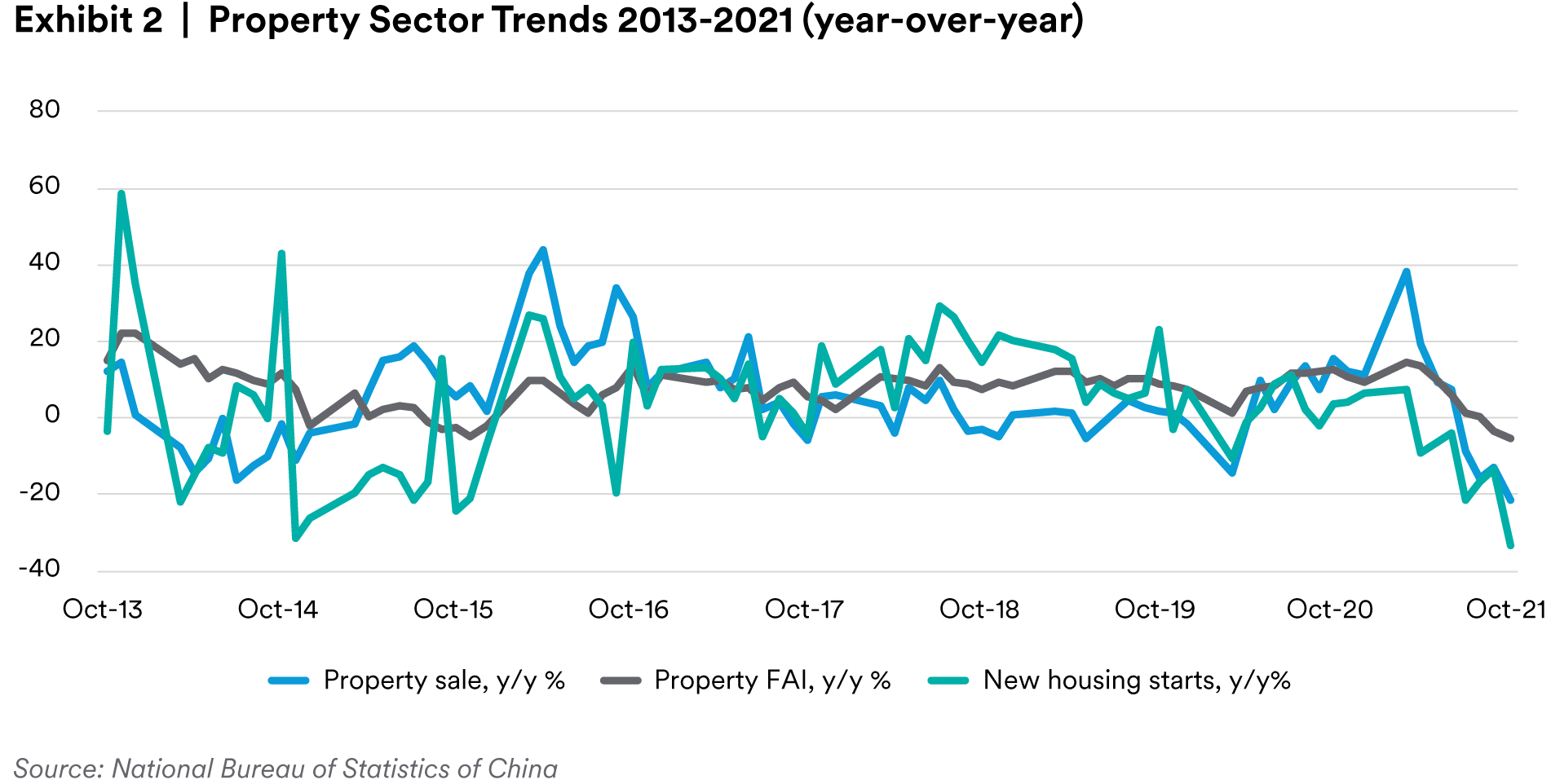

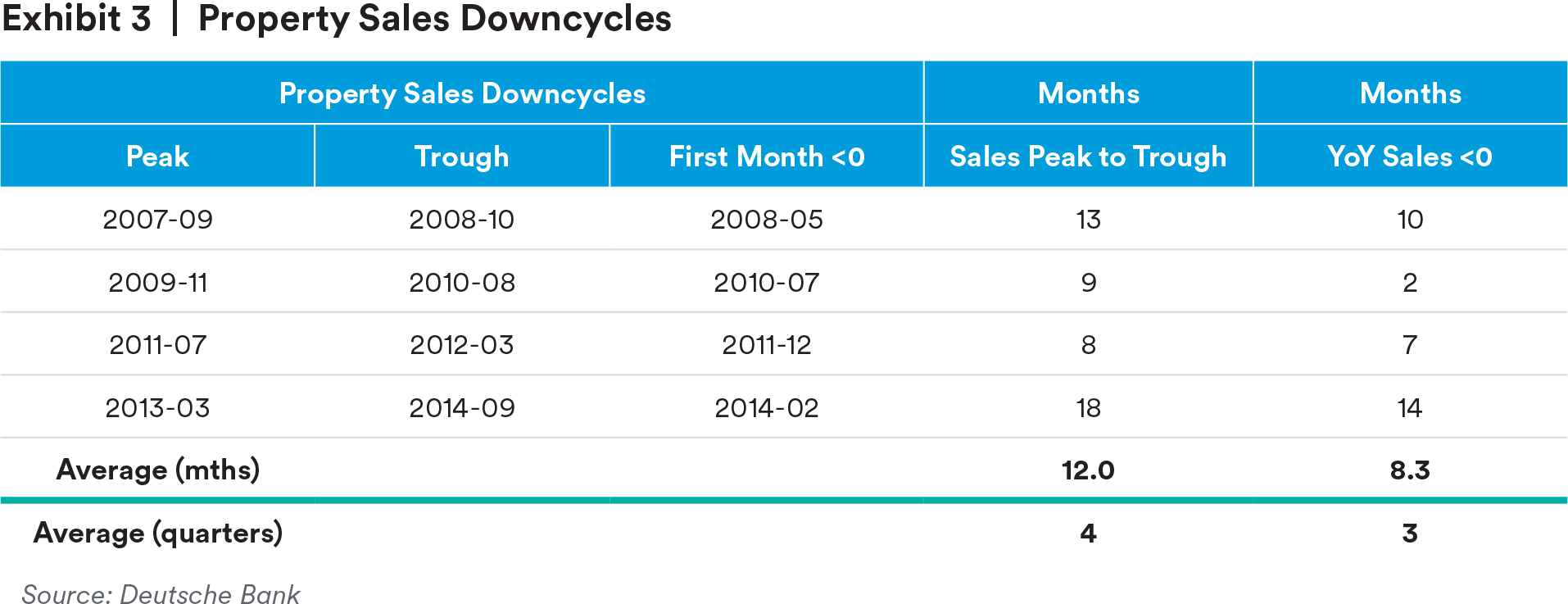

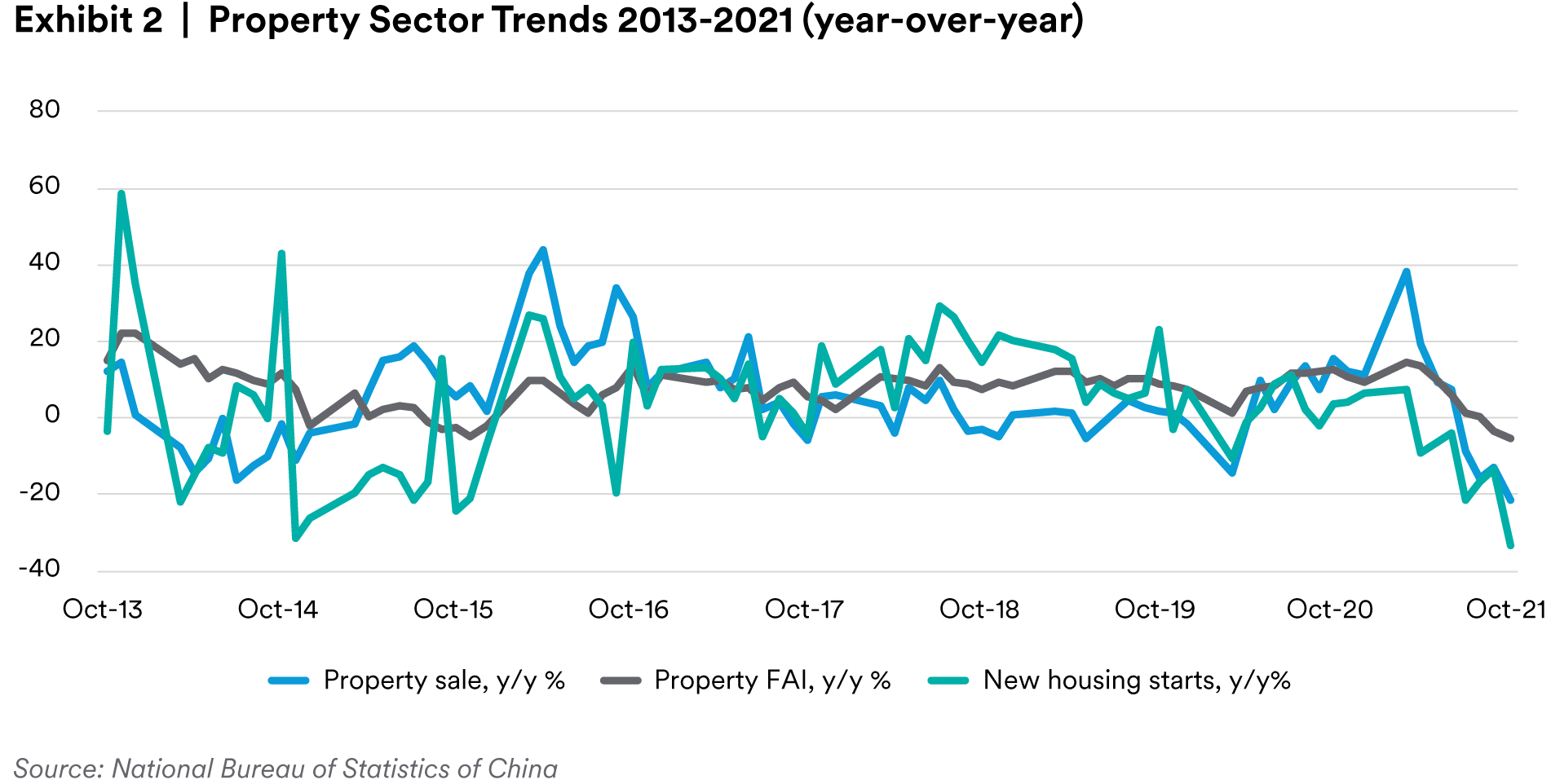

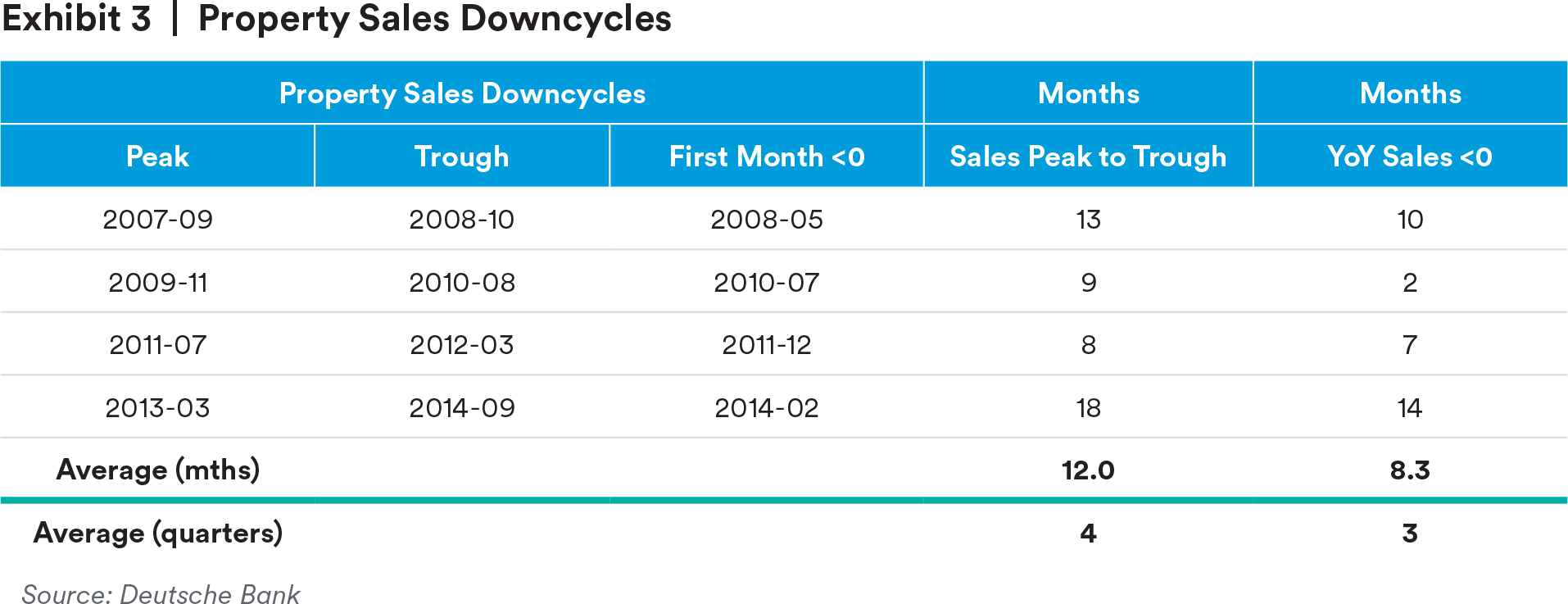

Double-digit contraction in property sales at least through mid-2022. This is China’s fourth major housing market downturn since 2007. Since mid-2021, troubles at Evergrande have shut down financing channels for developers and sapped market sentiment as home buyers became increasingly concerned about delivery and falling prices. As a result, property sales, new housing starts, and real estate investment have declined for eight consecutive months (Exhibit 2). Previous downturns show that it has historically taken three to six quarters, four quarters on average, for property sales to go from peak to trough (Exhibit 3). For this downcycle, property sales peaked in the first quarter of 2021 and turned negative in the third quarter on a year-over-year basis. Under our baseline scenario, we assume continued double-digit contraction through to mid-2022, bottoming at -25% year over year in the first quarter, followed by continued but shallower contraction in the second quarter and gradual recovery thereafter supported by more credit easing and marginal improvement in developer liquidity. Demand remained weak in November and December, with prices and sales falling nationwide, while several large developers face substantial maturing offshore debt over the next two to three months, some of which are expected to trigger orderly defaults. For full year 2022, we assume property sales contraction of -10% versus an expected +1.2% in 2021. As real estate investment has typically lagged property sales by one quarter, we believe the latter will provide little to no lift for GDP growth in 2022 (0% in 2022 versus +5% in 2021).

Multiple Growth Headwinds Nudging Policy Toward More Accommodation

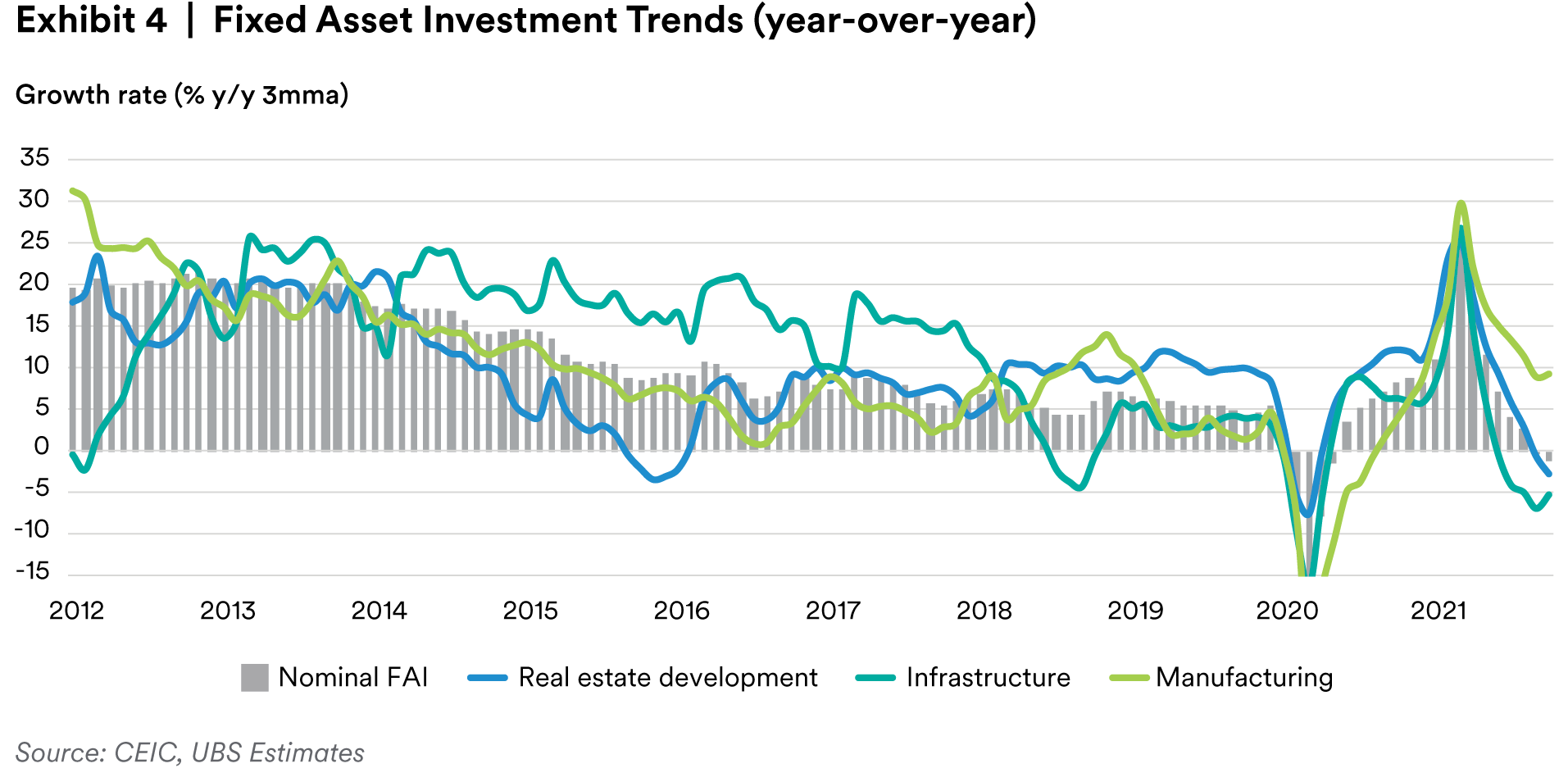

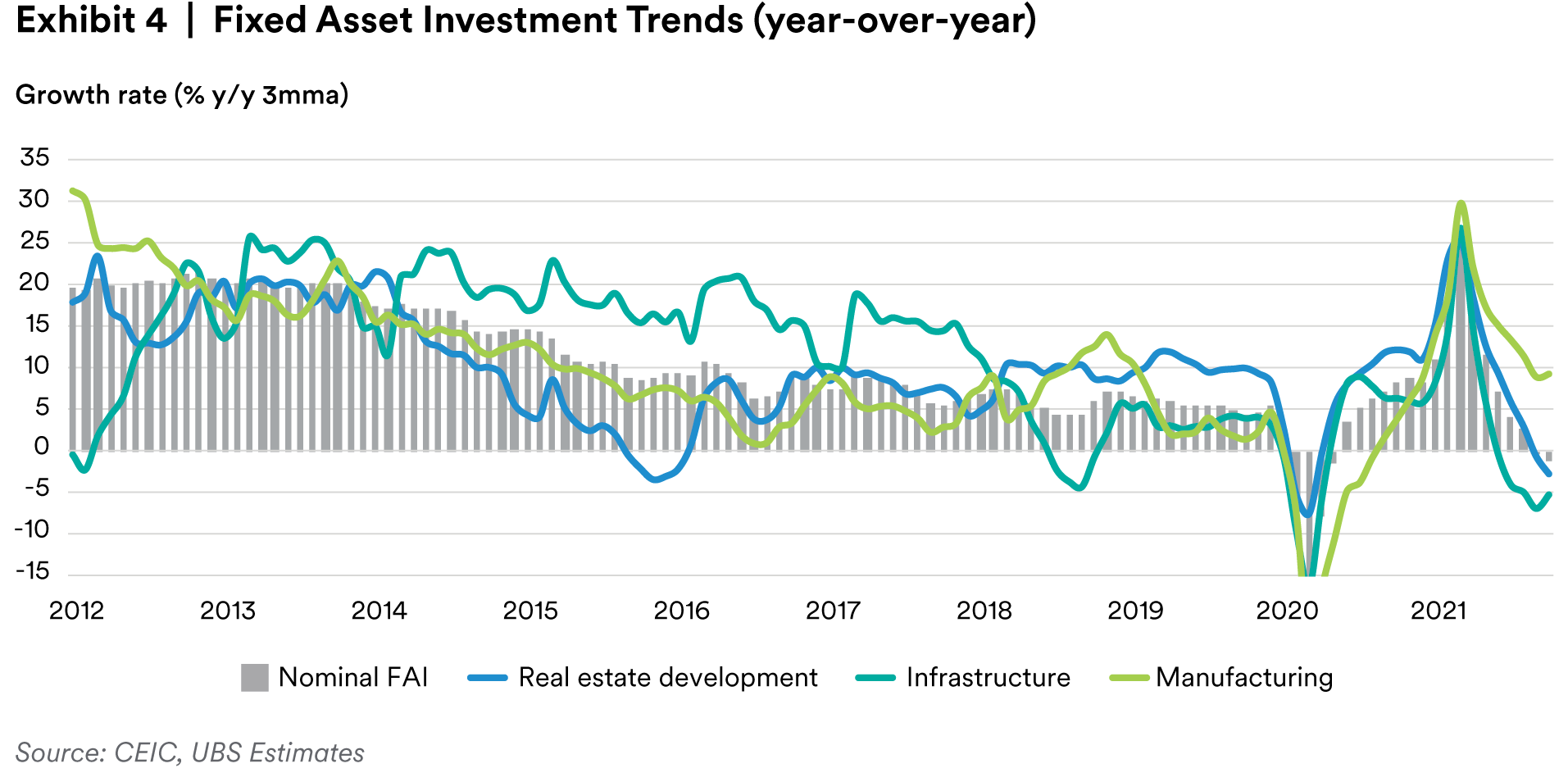

The property downturn has exacerbated already weak domestic demand. We downgraded our 2021 GDP growth forecast in mid-October to 7.8% from 8.2% given weak third quarter data and expectations for further slowdown in the fourth quarter. The property sector correction has major repercussions for the broader economy as it accounts for an estimated 30% of GDP while real estate investment has averaged around a quarter of total investment in recent years. Furthermore, falling property sales have crimped developers’ ability to buy land, squeezing local government finances and their capacity to carry out infrastructure projects because land sales account for about a third of their fiscal revenue. As a result, infrastructure investment has also fallen into contractionary territory this year (Exhibit 4). An additional headwind has come from weaker consumer confidence; household consumption and services sector activity have yet to recover from pre-pandemic levels given China’s sporadic outbreaks that have required strict adherence to Beijing’s Zero-Covid policies. To top it off, the economy has been jolted by a power crunch, exacerbated by Beijing’s stringent enforcement of energy consumption and emissions reduction targets.

Beijing is tiptoeing toward more policy accommodation. Beijing’s mantra of “stable house prices, stable land prices, stable market expectations” means that housing policies are no longer part of the counter-cyclical policy toolkit; the market has thus ruled out any major policy reversals for the property sector including the “Three Red Lines”. However, recent rhetoric and policy pronouncements clearly suggest that Beijing is becoming more concerned about the growth slowdown. In mid-November, Premier Li emphasized the “Six Stabilities” and “Six Guarantees” first introduced in July 2018 and April 2020 when the economy faced similar headwinds.2 In its most recent third quarter Monetary Policy Implementation report, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank, acknowledged downward pressures on GDP growth and pledged to “stabilize credit growth”. Since then, the PBOC announced a cut in banks’ Reserve Requirement Ratio (“RRR”) of 25 bps and rolled out low interest relending facilities to sectors supporting Beijing’s de-carbonization initiatives. The government’s Central Economic Work Conference in early December also set economic stabilization as a top priority for 2022. On the fiscal front, local governments have been ordered to use up their full year quota for special bond issuance more quickly, which should lead to an uptick in infrastructure spending before year end, as well a recovery in total credit growth from the October bottom.

More evidence of direct property sector support. Beijing’s rhetoric and actions around the Evergrande saga clearly suggest it wants to prevent a liquidity crunch and broader contagion in the property sector. Moreover, there is social risk if pre-paid properties are not delivered. In late-September, the PBOC and financial regulators requested that China’s banks relax tight credit controls on mortgage and developer loans. To give banks room to do so without breaching regulatory limits, regulators issued fresh quotas for banks to sell mortgage-backed securities. In addition, local governments have been ordered to help suspended property projects resume construction and prioritize delivery. Some early signs of relaxation on financing can be seen; new mortgage loans in October and November rose while a select number of state-owned developers have re-launched financing channels in the onshore bond market since mid-November. This policy fine-tuning has made clear Beijing’s intentions to prevent a liquidity crunch and hard landing in the property sector.

Possible Pain Thresholds and Likely Triggers for More Policy Easing Ahead

If forced to choose, we believe Beijing will give in to more policy support. Given Beijing’s policy regime shift, its pain threshold for slower growth has arguably increased versus previous tightening cycles, allowing it to push through its de-risking program without any major countercyclical easing YTD. That said, there are still limits to what Beijing can tolerate as China approaches the 20th Party Congress in the fourth quarter of 2022. At the end of the day, the property sector is “too big to fail” while macro, financial and social stability remain a top priority for Beijing. An over correction in the property sector would risk a hard landing in the economy leading to potential labor market dislocation, a scenario that Beijing would prefer to avoid in a sensitive political year. Around 40% of banking assets are directly or indirectly associated with the property sector and thus a sharp correction could also be a source of financial stability risk.3

A lagged policy response would be self-defeating. If a lagged policy response caused broader contagion and downside risks for the economy, Beijing would be forced to respond with more substantial monetary and fiscal policy support, including possible forbearance on the “Three Red Lines” for developers, more material relaxation of mortgage quotas and general unwinding other property curbs. This would ultimately undermine the original intention of Beijing’s de-risking program to reduce leverage and moral hazard risks. In our view, Beijing wants to remain ahead of the curve to avoid such outcomes. As such there are potential triggers that could galvanize more decisive policy support.

Labor market disruption. Another source of alarm would be significant weakening in the upstream sectors of the property supply chain including steel, cement, and heavy machinery, which would have negative spillover implications for the job market. According to JPMorgan, labor market conditions have already deteriorated in the form of job losses and wage cuts, particularly in sectors that have been affected by Beijing’s policy clampdowns such as property, coal, and education.4 One method of detecting labor market dislocations will be around the flow of migrant workers before and after the Lunar New Year holiday, using high frequency data to track travel, as well as anecdotal evidence.

A slowdown in export growth. Third quarter 2021 data showed that net exports contributed 19.5% of GDP growth in the first nine months of the year. This is very high by historical standards; net exports contribution to GDP has typically been below zero and thus a drag on China’s GDP growth over the last decade with some occasional exceptions. Strong exports have provided a welcome cushion for manufacturers as domestic demand has waned, while also creating a window of opportunity for Beijing to push its de-risking efforts and property curbs. Goods exports should hold up well given the approaching holiday season but could slow in the first half of 2022 as households in key export markets run-down their savings and consumption cools, while broader post-pandemic growth globally spurs more demand for services rather than goods.

Signposts for further easing, and what policy support is likely to entail

Reading the tea leaves. Several upcoming governmental meetings will offer insight into Beijing’s policy biases, providing more clarity around the timing of additional policy support. The next events to watch are the State Council and various ministerial work plan meetings in mid-January and the National People’s Congress (“NPC”) meeting in March. These events should begin to create a firmer narrative around the path of policy support ahead.

End of first quarter appears to be reasonable timing for more decisive policy support. Our baseline scenario assumes that property sales will experience their third and deepest quarterly double-digit contraction in the first quarter of 2022, which would appear a reasonable time to roll out more decisive policy support, particularly in view of the lagged effect of such support ahead of the 20th Party Congress. However, if our downside scenario emerged with a deeper downturn in coming months, including more defaults from developers and related sectors, we would assume more material and front-loaded policy support earlier in the first quarter of 2022.

More RRR cuts and re-lending facilities. Under our baseline scenario, Beijing’s policy playbook is one of “finetuning” to “stabilize rather than stimulate” the property sector and prevent sentiment from declining further.5 When more easing does come, the PBOC is likely to rely on its quantitative liquidity management tools, which would entail further RRR cuts, as well as more roll out of low interest relending facilities to support more challenged sectors. A cut to the 5-year Loan Prime Rate (“LPR”), upon which mortgages are priced, would also support housing demand. That said, we believe this is less likely near term so long as producer price inflation remains elevated. Should our downside scenario materialize, risking more spillover into the broader economy and labor market, an LPR cut could become part of the policy mix response.

More fiscal support supporting a recovery in credit growth. The recent push to accelerate local government special bond issuance is likely to be the beginning of a more counter-cyclical fiscal stance that will extend into 2022. This should entail a moderately wider central government fiscal deficit target of 3.2% next year versus an expected 2.9% in 2021, including tax incentives and subsidies to support consumption and promote technology upgrading. With a drop in land sales revenue for local governments, more proactive fiscal support will likely underpin infrastructure investment and provide an offset to what will be a very weak year for real estate investment. A higher quota for local government special bonds with front loaded first quarter issuance could in turn spur a moderate rebound in credit growth in the first half of 2022.

Summarizing the outlook for 2022 growth

Middle of the road growth in an important political year. We forecast 5.1% GDP growth for 2022, which is below consensus of 5.4%, lower than the pre-pandemic three-year average of 6.5% and at the lower end of the PBOC’s 5.0%-5.7% estimated potential growth range. Our forecast assumes a cyclical bottoming of GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2021 and first quarter of 2022 within a range of 2.5%-3.5% year over year followed by a modest pick-up thereafter, averaging 4% and 6% in the first and second halves of 2022 respectively. Importantly, our forecast assumes continued double-digit contraction in property sales through to mid-2022, bottoming at -25% year over year in the first quarter, but no hard landing in the property sector. Given the extent of the correction, we believe policy support will act to alleviate rather than fully offset slowing property-related activity, leading to little or no real estate investment growth next year. We do not ascribe to the more bearish views of 4%-4.5% GDP growth as this would entail a more severe property downturn and possible labor market dislocation, risking unintended consequences we believe Beijing would prefer to avoid in an important and sensitive political year.

No major growth engines next year, but enough to support a gradual recovery. Under our baseline forecast, increasingly supportive policy should help guide the property sector and economy toward a modest recovery in the second half of 2022. Growth would likely also enjoy some support from the manufacturing sector and household consumption. We feel manufacturing investment will likely bottom in the fourth quarter of 2021 and recover into the new year thanks to improved corporate profitability and waning energy shortages. As manufacturing investment accounts for around 40% of total investment in the economy, it could go some way (along with a policy-induced improvement in infrastructure investment) to help offset weakness in real estate investment next year.6 We believe household consumption should also begin to recovery more meaningfully; our baseline growth forecast assumes manageable labor market dislocations as policies help to prevent a hard landing in the property sector. Moreover, households are sitting on a decent pile of pandemic-fueled savings that are more likely to be deployed as the year plays out. That said, we still believe that consumption growth will remain below the pre-Covid annual average pace of 6.5% in view of Beijing’s continued adherence to Zero Covid policies ahead of the Winter Olympics and the 20th Party Congress.

Conclusion

The property sector’s recovery is the key wild card for the Chinese economy next year. Unless managed well, Beijing’s policy regime shift risks triggering an overcorrection and a hard landing in the economy. But given the sensitivities around an important political year and the self-defeating nature of a lagged policy response, we believe Beijing will ultimately succeed in managing a relatively smooth property sector correction as current ongoing incremental support broadens out further in the first quarter, ensuring a gradual but modest economic recovery ahead of the 20th Party Congress later next year. This year’s growth slowdown has been largely policy-induced, providing us with some confidence that Beijing can engineer a similar policy-driven growth recovery next year.

Perhaps more interesting is what the policy regime shift and Common Prosperity program will mean for China’s longer term growth prospects beyond 2022. Our prognosis for next year is largely based on policy tweaks that help to prevent downside scenarios for the economy. But over the longer term, the policymaking process is likely to become inherently more complex given the multiple economic, political, and social goals emerging from Beijing’s new and evolving policy framework. Against this backdrop, greater potential for policy misstep will likely bring increased risks for the economy.

This will be the subject of our next analysis.

Endnotes

1 Developers wanting to refinance are being assessed against three thresholds: 1) a 70% ceiling on liabilities to assets; 2) a 100% cap on net debt to equity; and 3) a cash to short-term borrowing ratio of at least one. Developers are categorized based on how many limits they breach, and their debt growth is capped accordingly. If a developer passes all three thresholds, it can increase its debt a maximum of 15% in the next year.

2 Premier Li stated that economic security can be achieved from stability on six fronts: employment, the financial sector, foreign trade, foreign investment, domestic investment, and expectations. The six guarantees refer to job security, basic living needs, operations of market entities, food and energy security, stable industrial and supply chains, and the normal functioning of primary-level governments.

3 As of June 2021. Citi “Evergrande’s Default Crunch is Unlikely to be China’s Lehman Moment” Judy Zhang, September 20, 2021

4 JP Morgan “Greater China 2022 Economic Outlook” Haibin Shu, November 29, 2021

5 Citigroup “Growth Hinges on Real Estate” Ligang Liu, November 23, 2021

6 UBS “Monthly Chartbook: China by the Numbers” Ning Zhang, November 24, 2021

Disclosure

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors. This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services.

The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

All investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results.

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address Level 34 One Canada Square London E14 5AA United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102- 0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”).

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

1 MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”) is MetLife, Inc.’s institutional management business and the marketing name for subsidiaries of MetLife that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/ or unaffiliated/third party investors, including: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), and MIM I LLC.